Writing and calling functions

Agenda for today:

Side effects

A function has a side effect if it does anything other than compute a return value, for instance, if it changes the values of other variables in the environment it is defined in, or adds variables to the environment.

We generally don't want functions to have side effects, because they make code more confusing and more difficult to test.

In R, functions can have side effects, but it is discouraged by both the language itself and by programming norms.

Remember that functions can see variables defined in the parent environments.

What they can't do is change the values of those variables (except with a special operator).

For example:

w = 12

f = function(y) {

d = 8

w = w + 1

y = y - 2

cat(sprintf("Value of w: %i", w))

h = function() {

return(d*(w+y))

}

return(h())

}

t = 4

f(t)

## Value of w: 13

## [1] 120

w

## [1] 12

It looks like the value of w changed inside the function, but the value in the global environment was not actually changed.

Primary exceptions to the no side effects rule:

The complement of the no side effects rule

No side effects says in part that functions shouldn't change variables in the global environment (or any other environment).

Your functions also should not read from environments other than the function's execution environment.

This rule isn't as strong/there are more exceptions, but in general all the variables your function uses should be given as arguments to the function.

Some rules for writing functions

"The first rule of functions is that they should be small. The second rule of functions is that they should be smaller than that."

Functions should do one thing. Multiple tasks = multiple functions.

Related functions should have consistent interfaces: if they take the same input, they should have the same arguments in the same order. If they make the same output, they should give output in the same way.

No side effects.

No magic numbers.

Example

Back to the birthday problem from the first week of class.

We wanted to know how many classes filled with randomly selected individuals we would have to attend before we found one where there were at least two pairs of people with the same birthday, and we wrote the following code to do one simulation:

days_in_year = 365

class_size = 20

num_classes = 0

while(TRUE) {

num_classes = num_classes + 1

birthdays = sample(1:days_in_year, class_size, replace = TRUE)

two_pairs = sum(table(birthdays) >= 2) >= 2

if(two_pairs) {

break

}

}

num_classes

## [1] 17

We want to perform simulations to get at the distribution of this random variable, so we have to run the same code over and over.

One option is to just take the code we had and wrap it in a for loop:

days_in_year = 365

class_size = 20

n_iter = 100

n_class_vector = rep(NA, n_iter)

for(i in 1:n_iter) {

num_classes = 0

while(TRUE) {

num_classes = num_classes + 1

birthdays = sample(1:days_in_year, class_size, replace = TRUE)

two_pairs = sum(table(birthdays) >= 2) >= 2

if(two_pairs) {

break

}

}

n_class_vector[i] = num_classes

}

A better option is to make the simulation code into its own function:

## simulates one draw of our random variable

simulate_n_classes = function(class_size, days_in_year = 365) {

num_classes = 0

while(TRUE) {

num_classes = num_classes + 1

birthdays = sample(1:days_in_year, class_size, replace = TRUE)

two_pairs = sum(table(birthdays) >= 2) >= 2

if(two_pairs) {

break

}

}

return(num_classes)

}

## simulate many draws of the random variable

n_class_vector = replicate(n = 100, simulate_n_classes(class_size = 20))

Maybe next we're interested in how the distribution changes with class size.

Let's make a function that computes the average number of classes we need to go to before we get two pairs of birthdays:

get_expected_num_classes = function(class_size, days_in_year = 365, n_iter = 100) {

## simulating n_iter draws from simulate_n_classes

sims = replicate(n = n_iter, simulate_n_classes(class_size = class_size, days_in_year = days_in_year))

return(mean(sims))

}

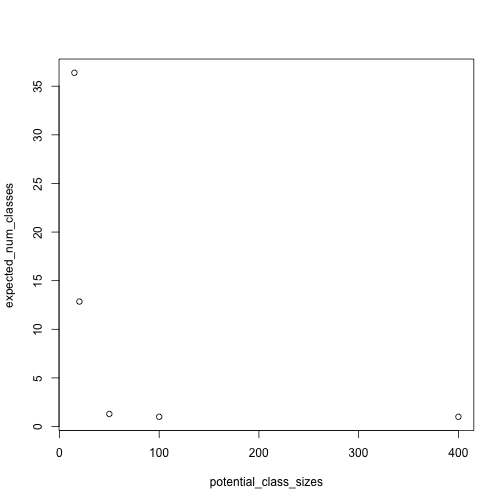

Once we have that function, we can compute the expectation for a range of class sizes and make a plot:

plot_expected_num_classes = function(potential_class_sizes, days_in_year = 365, n_iter = 100) {

## compute expected class size for every value of potential_class_sizes

expected_num_classes = rep(NA, length(potential_class_sizes))

for(i in 1:length(potential_class_sizes)) {

expected_num_classes[i] =

get_expected_num_classes(potential_class_sizes[i], days_in_year = days_in_year, n_iter = n_iter)

}

plot(expected_num_classes ~ potential_class_sizes)

}

plot_expected_num_classes(c(15, 20, 50, 100, 400))

That's about as far as we want to go in that direction.

Let's ask a new question: how does the birthday problem change if different days of the week are more or less favored?

We can modify our simulation code to simulate from uneven probabilities. We'll want to give the probabilities as an argument to the function and check that they are valid.

simulate_n_classes = function(class_size, day_probabilities) {

num_classes = 0

## checking that day_probabilities is actually a vector of probabilities

stopifnot(sum(day_probabilities) == 1 && all(day_probabilities >= 0))

while(TRUE) {

num_classes = num_classes + 1

birthdays = sample(1:length(day_probabilities), class_size, replace = TRUE, prob = day_probabilities)

two_pairs = sum(table(birthdays) >= 2) >= 2

if(two_pairs) {

break

}

}

return(num_classes)

}

get_expected_num_classes = function(class_size, day_probabilities, n_iter = 100) {

## simulating n_iter draws from simulate_n_classes

sims = replicate(n = n_iter, simulate_n_classes(class_size = class_size, day_probabilities))

return(mean(sims))

}

Then we can use the function we've created to see how the expected number of classes changes as the relative probability of weekday vs. weekend birth changes:

## make day probabilities by repeating two small numbers followed by five big numbers until we get 365, then divide by the sum to get probabilities

day_probabilities = rep(c(rep(1,2), rep(3,5)), length.out = 365)

day_probabilities = day_probabilities / sum(day_probabilities)

# compare values when the weekdays are more likely to when everything is equal

get_expected_num_classes(20, day_probabilities)

## [1] 10.45

get_expected_num_classes(20, rep(1 / 365, 365))

## [1] 11.64

A nice exercise would be to make a function that created these probabilities, taking as a parameter the relative probability of weekend vs. weekday. That would allow us to explore the distribution more easily, instead of with the ugly code on the last two lines.