Stat 470/670 Lecture 8: Flexible modeling for

bivariate data

Julia Fukuyama

Today

- Review linear regression/parametric smoothers

Regression review

Task 1: How do we use multiple regression to fit non-linear functions

of predictors?

Task 2: How can we use weights in regression to do local fits?

Generalizations of the regression problem: Weighted least

squares

If we have more faith in some points than others, or if we simply

want to exclude some points, we can perform weighted linear

regression.

Let \(w_i\), \(i = 1,\ldots, n\) be non-negative

values.

In weighted regression, we find \(\beta_0,

\ldots, \beta_p\) to minimize

\[

\sum_{i=1}^n w_i (y_i - (\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \cdots + \beta_p

x_{ip}))^2

\]

Or, in matrix notation: \[

\|\mathbf W^{1/2} (\mathbf y - \mathbf X \mathbf \beta)\|_2^2

\] where \(\mathbf W^{1/2}\) is

an \(n \times n\) diagonal matrix with

\(w_i^{1/2}\) as the \(i\)th diagonal element.

Properties:

Setting \(w_i = 0\) is

equivalent to omitting the \(i\)th data

point from the analysis.

Setting all of the \(w_i\)’s

equal to \(1\), or all the equal to the

same positive value, leads to the same coefficient estimates as standard

linear regression.

Heuristically, points with higher values of \(w_i\) have higher “weight” in the

regression estimation: the line is penalized more for deviating from

those points, and so the fitted line will tend to track points with high

weights more closely than points with low weights.

References

If you feel like you need to brush up on this, a good reference is

Weisberg, Applied Linear Regression.

- Section 3.4 of Weisberg describes the matrix notation version of

multiple regression.

- Chapter 6 of Weisberg describes polynomial regression and indicator

matrices for factor variables.

Smoothing

Reading: Cleveland pp. 91-110

Why do we want to smooth?

If we have a lot of data/noise, the smoother allows us to see

what we can’t in a scatterplot of the raw data.

If we want to compare multiple sets of points, the smoother

simplifies the description and allows us to make the comparison between

the “main effects” in the data without our eye being distracted by the

noise.

Non-EDA: If we want to predict or estimate true underlying values

from noisy data, smoothers often help. Remember though, if this is your

purpose, you should still do the exploratory analysis to decide what

type of smoother to use, whether there should be breaks or jumps in the

smoother, or if any other weird things are happening.

LOESS

LOESS, or local regression, builds on standard regression. The setup

is:

- We have bivariate data, so pairs \((y_i,

x_i)\), \(i = 1,\ldots,

n\).

- We want to estimate the mean \(E(Y \mid

X)\). We think this is a smooth function of \(X\), but we don’t know what the form of

that function is.

The idea is that since the mean function is smooth, it can be

approximated with a linear or low-order polynomial function in small

regions.

LOESS: details

The way we transform this intuition into a concrete procedure is to

use weighted least squares.

LOESS has two parameters, \(\alpha\)

(the span), and \(\lambda\), the degree

of the local polynomial.

To find the value of the LOESS smoother at a point \(x_0\), we first define weights for all of

the samples: \[

w_i(x_0) = T(\Delta_i(x_0) / \Delta_{(q)}(x_0))

\] where \(\Delta_i(x_0) = |x_i -

x_0|\), \(\Delta_{(i)}(x_0)\)

are the ordered values of \(\Delta_{i}(x_0)\), and \(q = \alpha n\), rounded to the nearest

integer.

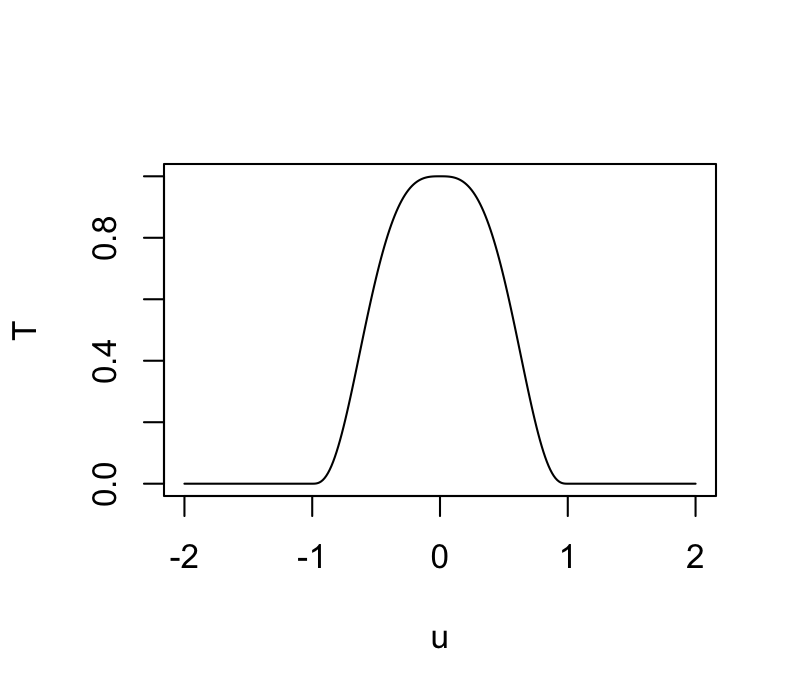

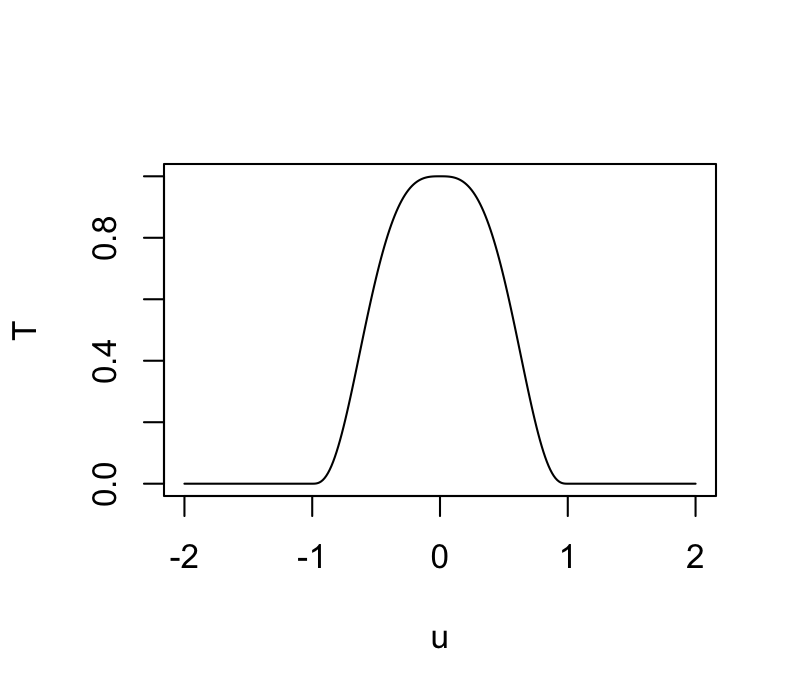

\(T\) is the tricube weight function

(invented by Tukey!): \[

T(u) = \begin{cases}

(1 - |u|^3)^3 & |u| \le 1 \\

0 & |u| > 1

\end{cases}

\]

These weights are then used in a local regression.

If \(\lambda = 1\), we find \(\hat \beta_0\), \(\hat \beta_1\) to minimize the weighted

least squares criterion, \[

(\hat \beta_0, \hat \beta_1) = \text{arg min}_{(\beta_0, \beta_1)}

\sum_{i=1}^n w_i (y_i - (\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i))^2,

\]

and the fitted value for the LOESS smoother at \(x_0\) is \(\hat

\beta_0 + \hat \beta_1 x_0\).

If \(\lambda = 2\), we use quadratic

regression, e.g. find \(\hat \beta_0\),

\(\hat \beta_1\), \(\hat \beta_2\) to minimize the weighted

least squares criterion, \[

(\hat \beta_0, \hat \beta_1, \hat \beta_2) = \text{arg min}_{(\beta_0,

\beta_1, \beta_2)} \sum_{i=1}^n w_i (y_i - (\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i +

\beta_2 x_i^2))^2,

\]

and the fitted value for the LOESS smoother at \(x_0\) is \(\hat

\beta_0 + \hat \beta_1 x_0 + \hat \beta_2 x_0^2\).

The analogous procedure works for any integer value of \(\lambda\).

The procedure described above gives a fitted value of the smoother at

one point; and we need to do all the weight and coefficient computations

for every point at which we want to evaluate the smoother.

LOESS in R

We’ll look at the economics dataset (in ggplot2).

It looks like this:

## # A tibble: 574 × 6

## date pce pop psavert uempmed unemploy

## <date> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1967-07-01 507. 198712 12.6 4.5 2944

## 2 1967-08-01 510. 198911 12.6 4.7 2945

## 3 1967-09-01 516. 199113 11.9 4.6 2958

## 4 1967-10-01 512. 199311 12.9 4.9 3143

## 5 1967-11-01 517. 199498 12.8 4.7 3066

## 6 1967-12-01 525. 199657 11.8 4.8 3018

## 7 1968-01-01 531. 199808 11.7 5.1 2878

## 8 1968-02-01 534. 199920 12.3 4.5 3001

## 9 1968-03-01 544. 200056 11.7 4.1 2877

## 10 1968-04-01 544 200208 12.3 4.6 2709

## # ℹ 564 more rows

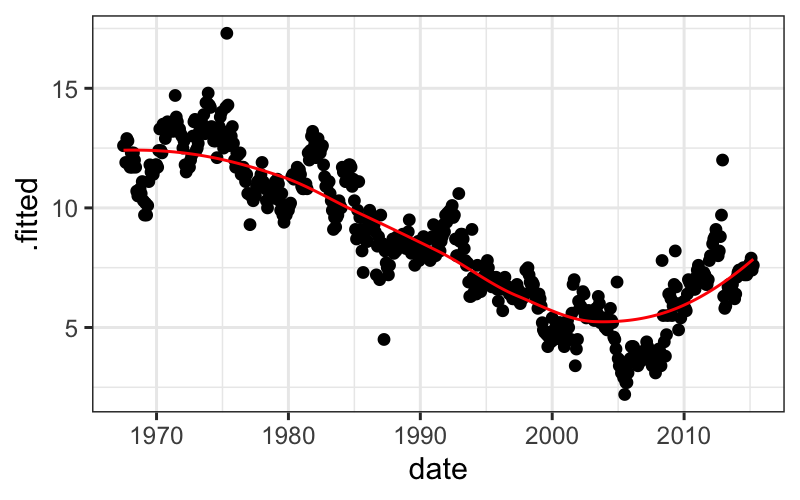

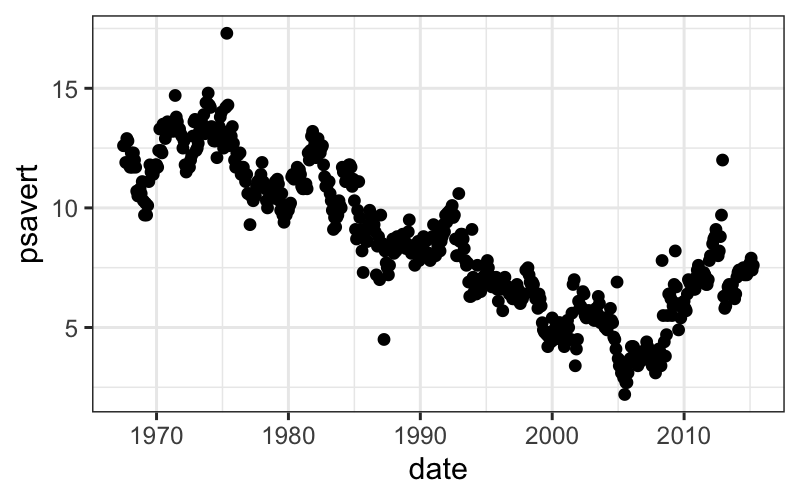

Let’s look at how psavert changes over time using a

scatterplot:

ggplot(economics) + geom_point(aes(x = date, y = psavert))

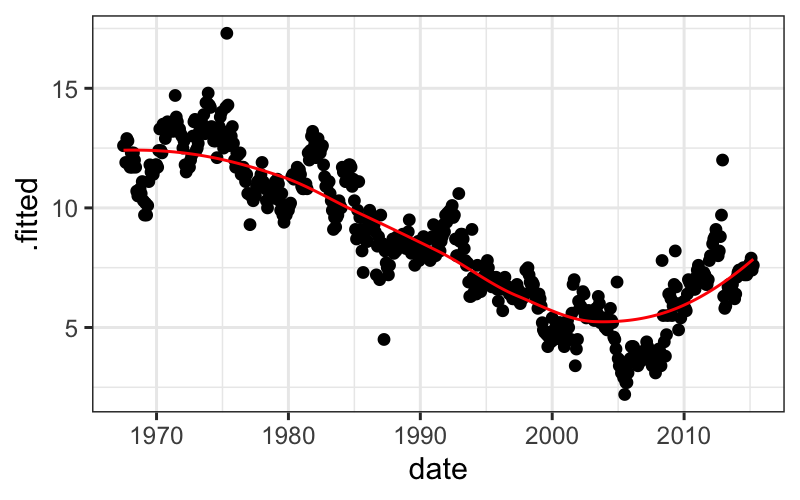

We’ll try smoothing here, but first note two tricky things about this

particular example:

The loess function doesn’t work well with

date class predictors, so we need to change date to

numeric.

When we plot the output, we want to plot the original date on the

x-axis, but augment by default only gives us the variables

that were used in the model (date_numeric and

psavert). To get a data frame with all the original

variables, we need to pass augment the extra argument

data = economics.

economics = economics %>% mutate(date_numeric = as.numeric(date))

l.out = loess(psavert ~ date_numeric, data = economics)

ggplot(augment(l.out, data = economics), aes(x = date, y = .fitted)) +

geom_point(aes(y = psavert)) + geom_line(color = "red")