Stat 470/670 Lecture 5: Building Simple Models

Julia Fukuyama

Today

- Build and critique simple models

- We’ve presented a lot of visualization methods for univariate data

simply as visualization methods, but they can also be thought of as

model validation techniques. e.g. a QQ plot is for checking normality of

a distribution.

- From other statistics classes, you know how to infer parameter

values and test hypotheses. Those parameter estimates and the

corresponding tests are valid given certain assumptions about the data.

Today we’re going to talk about how to check whether those assumptions

hold, how to try to make the data to fit those assumptions if they don’t

hold, and what to do if even the transformations don’t work.

Linear models

From your earlier statistics courses, you remember linear models.

Recall the assumptions for a linear model:

- Same variance of errors within each group (homoscedasticity)

Singer example

Reading: Cleveland pp. 34-41.

Load our standard libraries:

library(lattice)

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyverse)

## ── Attaching packages ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse 1.3.2 ──

## ✔ tibble 3.1.8 ✔ dplyr 1.0.10

## ✔ tidyr 1.2.1 ✔ stringr 1.5.0

## ✔ readr 2.1.3 ✔ forcats 0.5.2

## ✔ purrr 0.3.5

## ── Conflicts ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

## ✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

## ✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

Singer height = Average height for their voice part + some error

If you’ve taken S431/631 or a similar regression course, you might

recognize this as a special case of a linear model. If you haven’t,

well, it doesn’t really matter much except we can use the

lm() function to fit the model. The advantage of this is

that lm() easily splits the data into fitted

values and residuals:

Observed value = Fitted value + residual

Let’s get the fitted values and residuals for each voice part:

singer_lm = lm(height ~ 0 + voice.part, data=singer)

We can extract the fitted values using

fitted.values(singer.lm) and the residuals with

residuals(singer.lm) or singer.lm$residuals.

For convenience, we create a data frame with two columns: the voice

parts and the residuals.

singer_res = data.frame(voice_part = singer$voice.part, residual = residuals(singer_lm))

We can also do this with group_by and

mutate:

fits = singer %>%

group_by(voice.part) %>%

mutate(fit = mean(height),

residual = height - mean(height))

Does the linear model fit?

To asssess whether the linear model is a good fit to the data, we

need to know whether the errors look like they come from normal

distributions with the same variance.

The residuals are our estimates of the errors, and so we need to

check both normality and homoscedasticity.

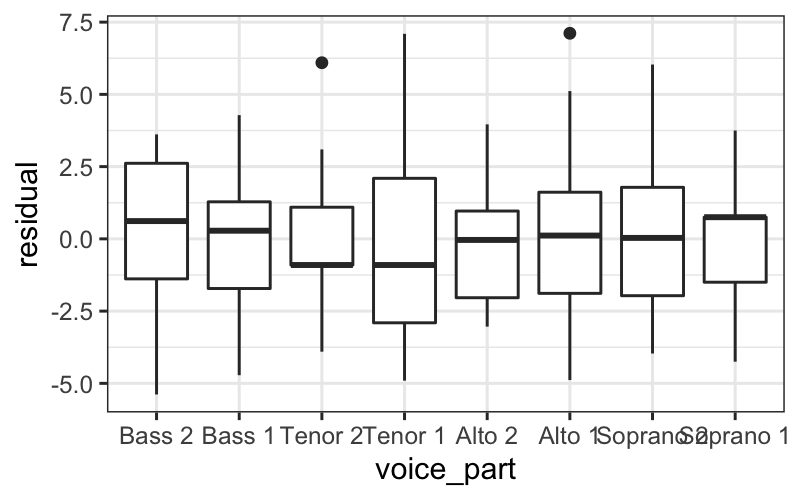

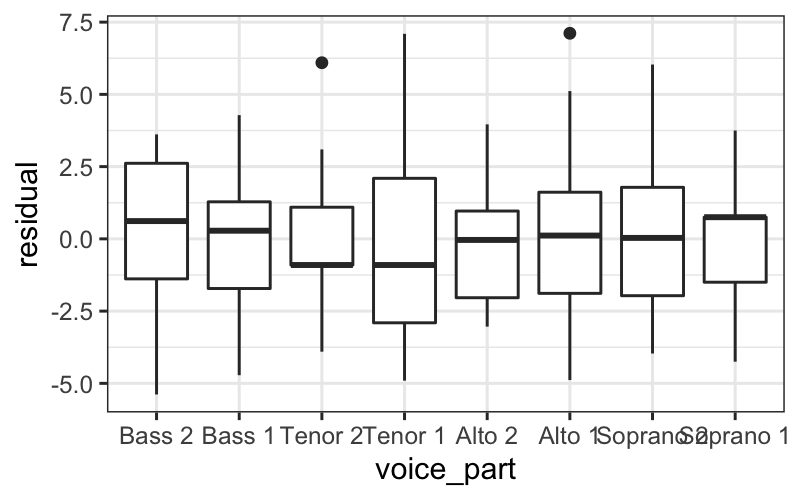

Homoscedasticity

There are a few ways we can look at the residuals. Side-by-side

boxplots give a broad overview:

ggplot(singer_res, aes(x = voice_part, y = residual)) + geom_boxplot()

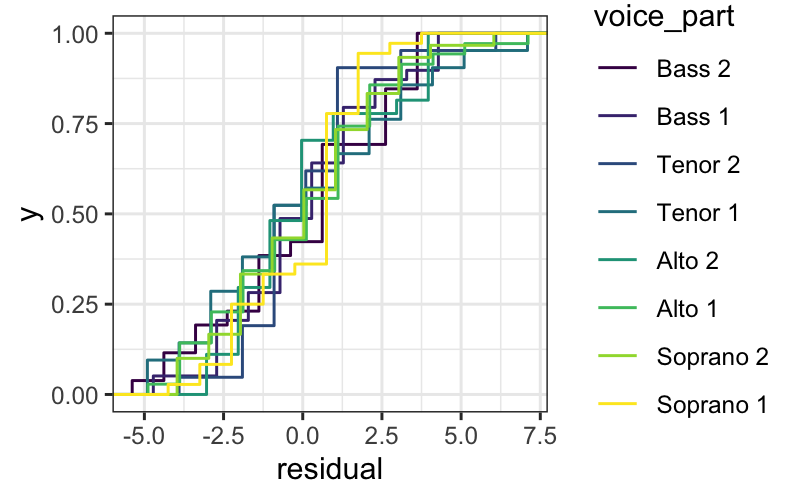

We can also look at the ecdfs of the residuals for each voice

part.

ggplot(singer_res, aes(x = residual, color = voice_part)) + stat_ecdf()

From these plots, it seems like the residuals in each group have

approximately the same variance.

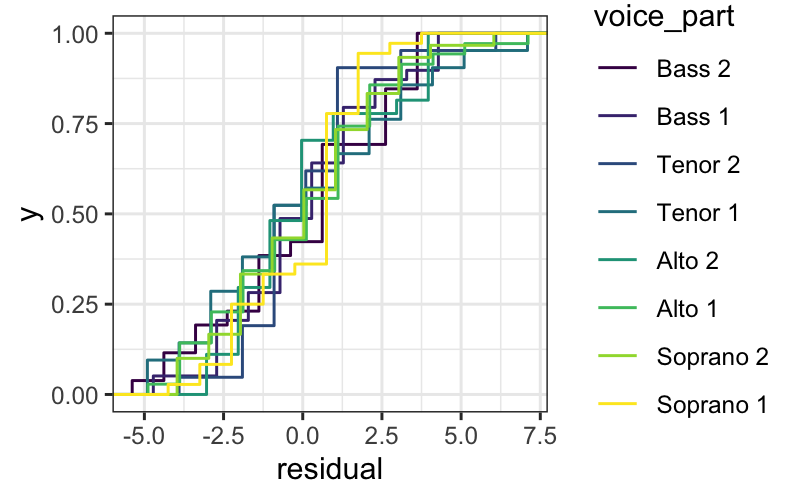

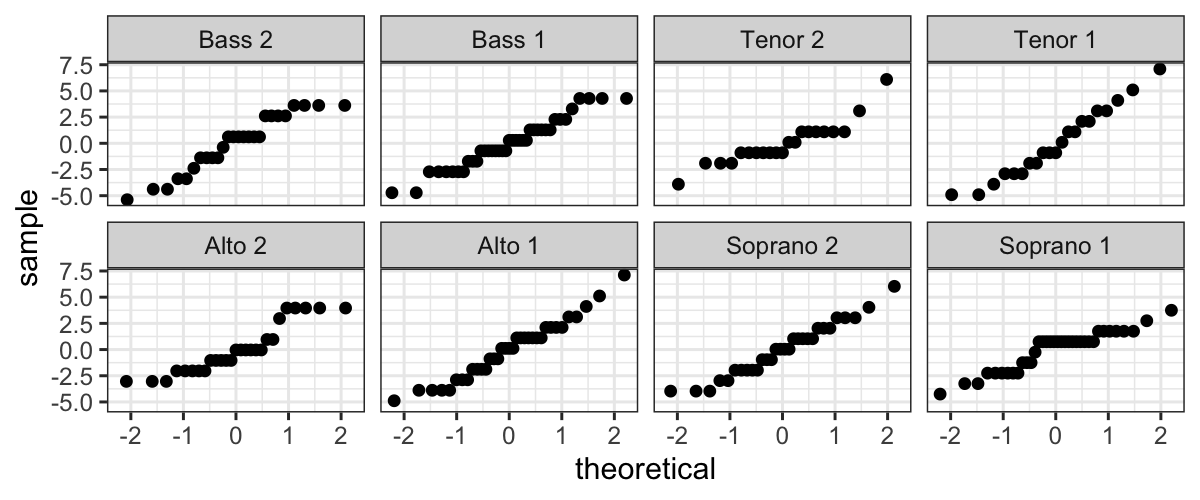

Normality

We also want to examine normality of the residuals, broken up by

voice part. We can do this by faceting:

ggplot(singer_res, aes(sample = residual)) +

stat_qq() + facet_wrap(~ voice_part, ncol=4)

Not only do the lines look reasonably straight, the scales look

similar for all eight voice parts. This suggests a model where all of

the errors are normal with the same standard deviation. This is

convenient because it is the form of a standard linear model:

Singer height = Average height for their voice part + Normal(\(0, \sigma^2\)) error.

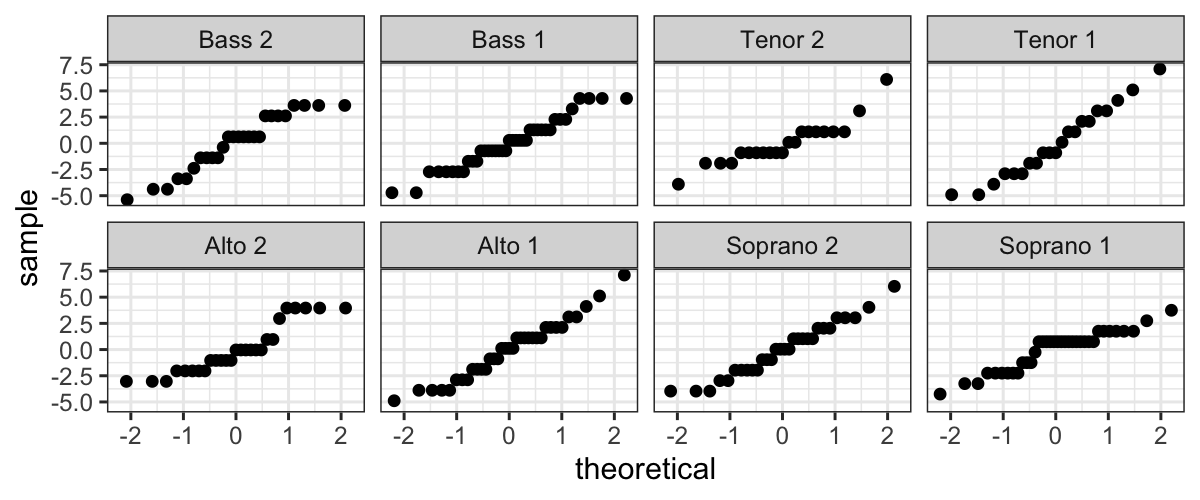

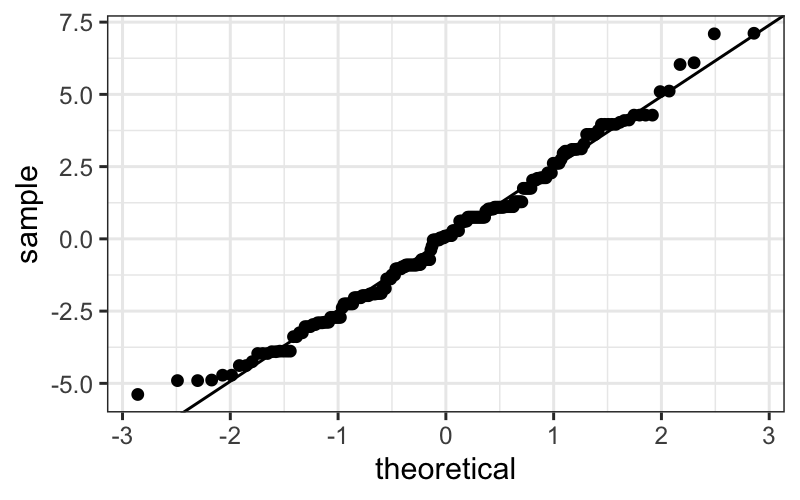

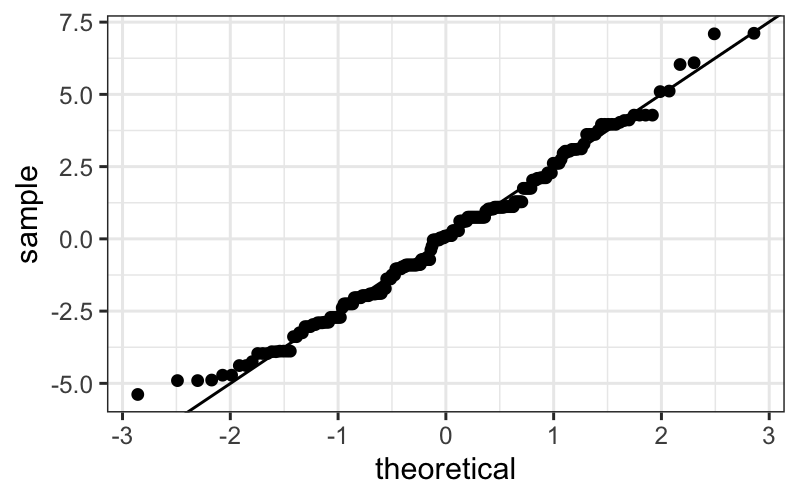

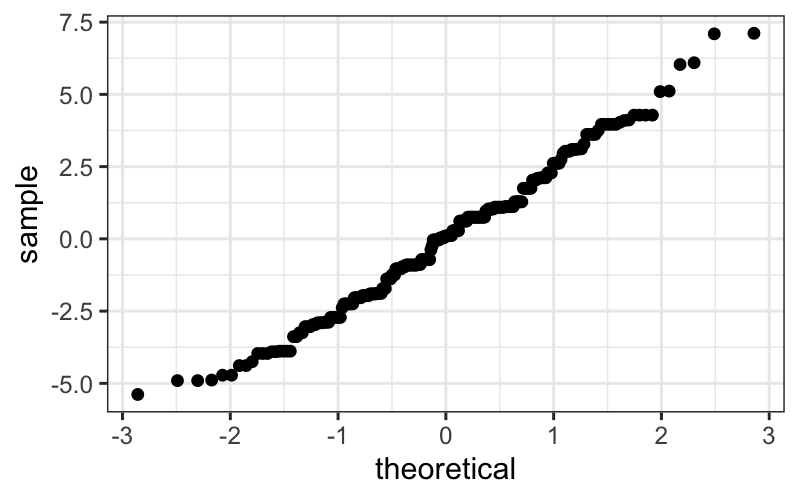

Normality of pooled residuals

If the linear model holds, then all the residuals come from the same

normal distribution.

We’ve already checked for normality of the residuals within each

voice part, but to get a little more power to see divergence from

normality, we can pool the residuals and make a normal QQ plot of all

the residuals together.

ggplot(singer_res, aes(sample = residual)) +

stat_qq()

It’s easier to check normality if we plot the line that the points

should fall on: if we think the points come from a \(N(\mu, \sigma^2)\) distribution, they

should lie on a line with intercept \(\mu\) and slope \(\sigma\) (the standard deviation).

In the linear model, we assume that the mean of the error terms is

zero. We don’t know what their variance should be, but we can estimate

it using the variance of the residuals.

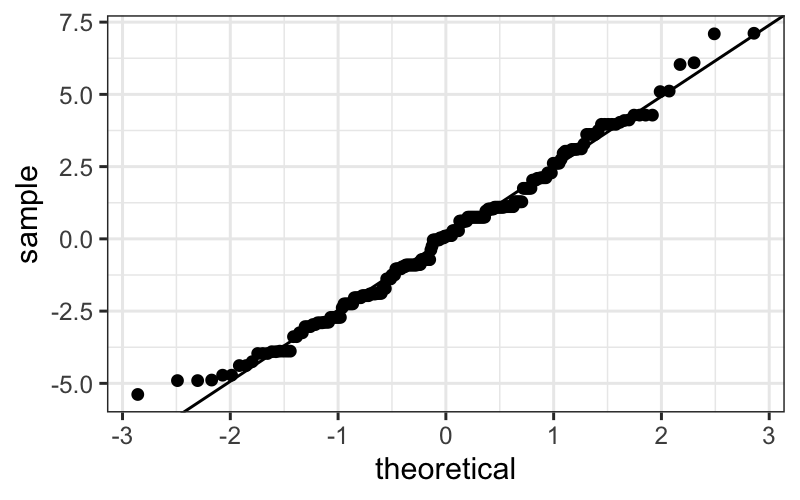

Therefore, we add a line with the mean of the residuals (which should

be zero) as the intercept, and the SD of the residuals as the slope.

This is:

ggplot(singer_res, aes(sample = residual)) +

stat_qq() +

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = sd(singer_res$residual))

The actually correct way

Pedantic note: We should use an \(n-8\) denominator instead of \(n-1\) in the SD calculation for degrees of

freedom reasons. We can get this directly from the linear model:

## [1] 2.465049

round(summary(singer_lm)$sigma, 3)

## [1] 2.503

However, the difference between this and the SD above is

negligible.

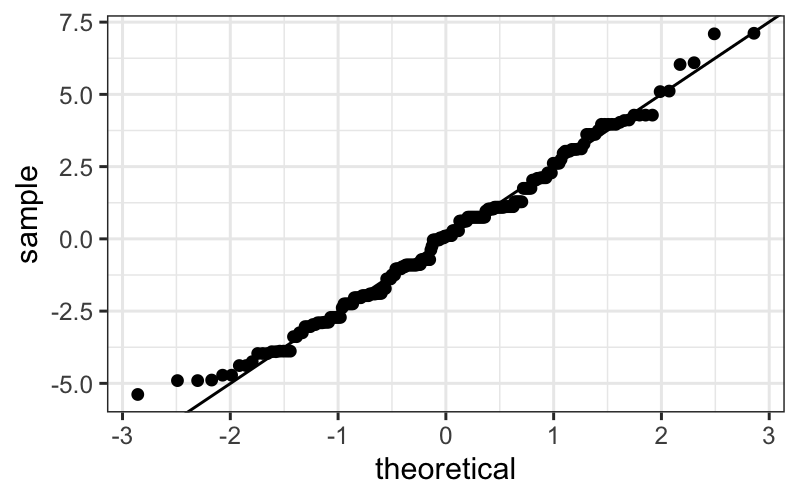

Add the line:

ggplot(singer_res, aes(sample = residual)) +

stat_qq() + geom_abline(intercept = mean(singer_res$residual), slope=summary(singer_lm)$sigma)

The straight line isn’t absolutely perfect, but it’s doing a pretty

good job.

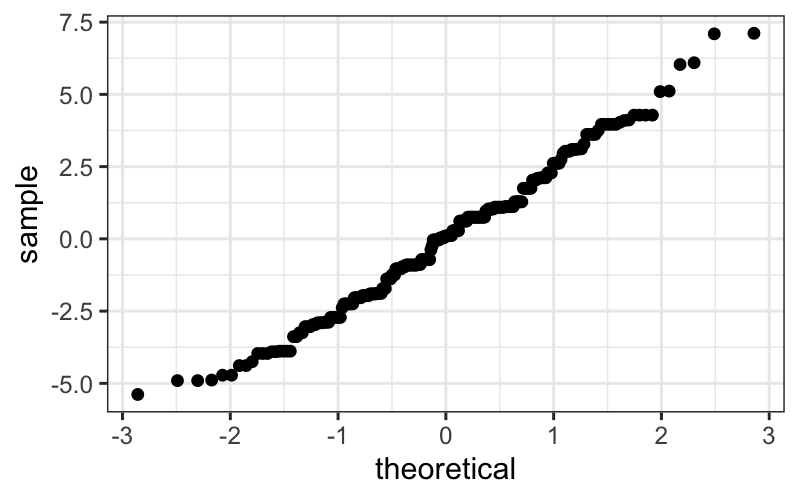

Our final model

Since the errors seem to be pretty normal, our final model is:

Singer height = Average height for their voice part + Normal(\(0, 2.5^2\)) error.

Note: While normality (or lack thereof) can be important for

probabilistic prediction or (sometimes) for inferential data analysis,

it’s relatively unimportant for EDA. If your residuals are about normal

that’s nice, but as long as they’re not horribly skewed they’re probably

not a problem.

What have we learned?

About singers:

- We’ve seen that average height increases as the voice part range

decreases.

- Within each voice part, the residuals look like they come from a

normal distribution with the same variance for each voice part. This

suggests that there’s nothing further we need to do to explain singer

heights: we have an average for each voice part, and there is no

suggestion of systematic differences beyond that due to voice part.

About data analysis:

- We can use some of our univariate visualization tools, particularly

boxplots and ecdfs, to look for evidence of heteroscedasticity.

- We can use normal QQ plots on both pooled and un-pooled residuals to

look for evidence of non-normality.

- If we wanted to do formal tests or parameter estimation for singer

heights, we would feel pretty secure using results based on normal

theory.

Example 2: Bin Packing

Reading: Cleveland pp. 68-79.

A classic

problem in computer science involves how to most efficiently pack

objects of different volumes into containers so as to minimize the

number of containers used.

The bin packing problem is NP hard, but some heuristic algorithms

perform well.

One such algorithm is the first fit descending algorithm, where the

objects are considered in decreasing order of size, and each object is

put into the first container in which it fits.

Our dataset

Some investigators were interested in the performance of this

algorithm, and in particular how much excess volume is available when

this algorithm is run on different numbers of objects. To this end, they

ran a simulation experiment in which simulated \(n\) objects with volumes drawn from a

uniform distribution on \([0, .8]\),

ran the first fit descending algorithm to pack those objects into

containers of volume 1, and computed how much empty volume remained in

the containers after the algorithm had completed. They repeated the

simulation 25 times for \(n = 125, 250, 500,

1000, \ldots, 128000\).

The results of the experiment are in lattice.RData, in a

data frame bin.packing.

The data frame contains two variables:

empty.space: The amount of empty space.

number.runs: The number of randomly generated objects

(this is poorly named).

We are interested in how empty space depends on the number of

randomly generated objects (number.runs).

Bin packing

Let’s start off by loading and looking at the data.

load("lattice.RData")

head(bin.packing)

## empty.space number.runs

## 1 1.577127 125

## 2 1.242906 125

## 3 1.389246 125

## 4 0.636317 125

## 5 0.443350 125

## 6 1.522842 125

table(bin.packing$number.runs)

##

## 125 250 500 1000 2000 4000 8000 16000 32000 64000 128000

## 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25

summary(bin.packing$empty.space)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.4019 1.2206 1.7590 1.9959 2.4994 6.7839

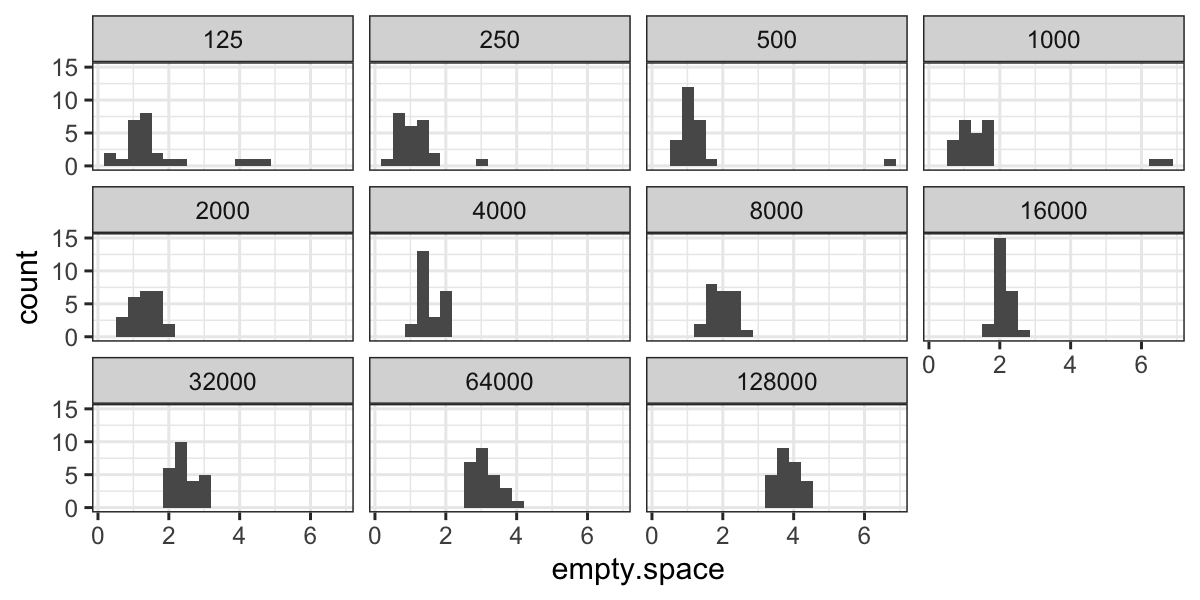

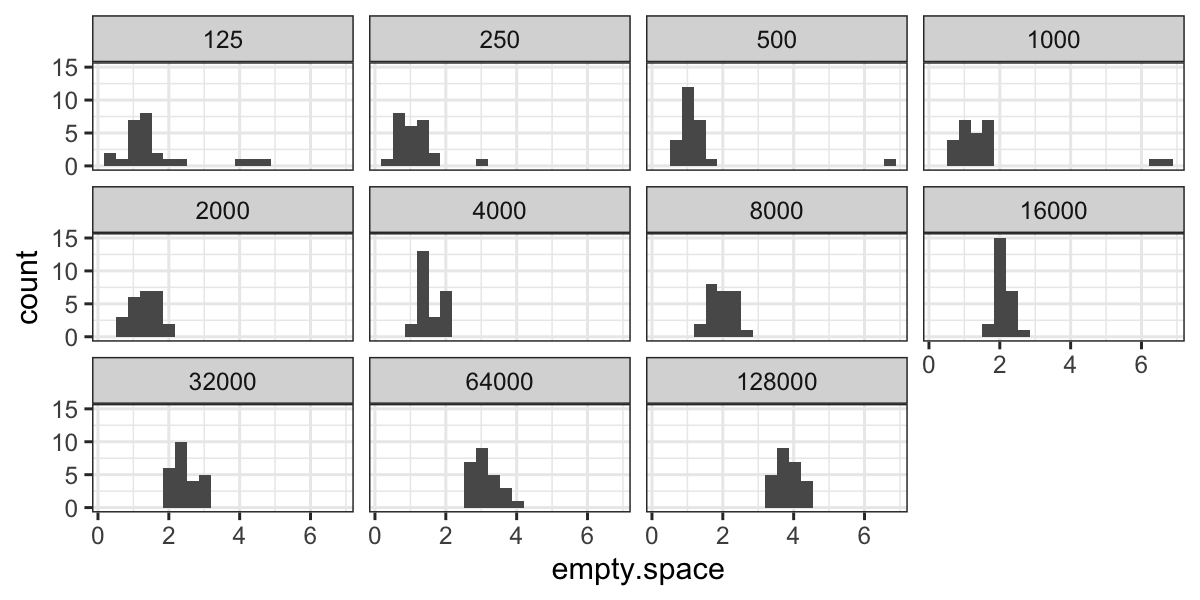

We can look at the distributions of empty space for every value of

number.runs:

ggplot(bin.packing, aes(x = empty.space)) + geom_histogram(bins = 20) +

facet_wrap(~ factor(number.runs))

From the histograms we notice a couple of outliers for small values

of number.runs

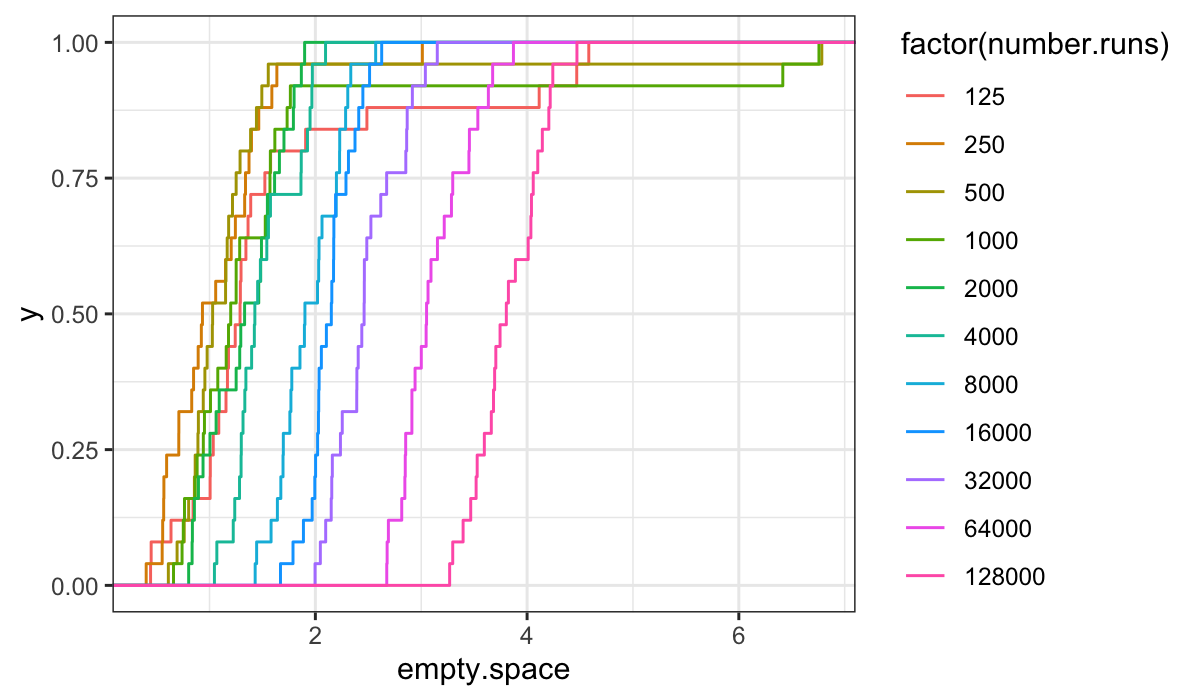

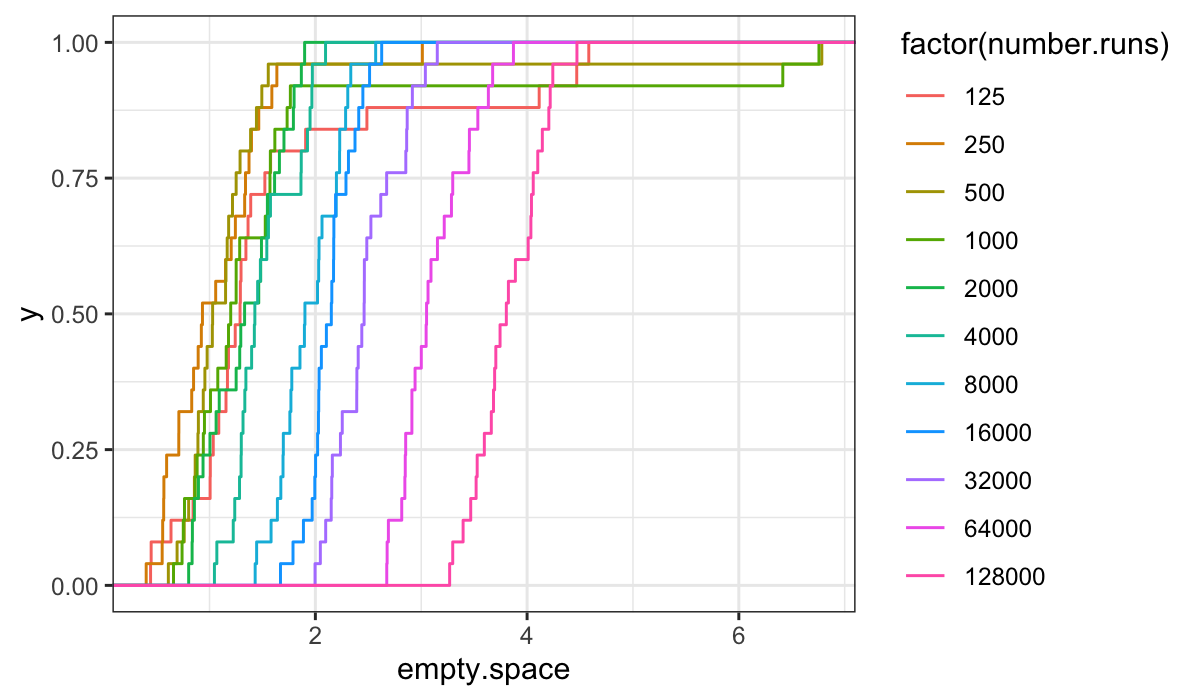

ecdfs:

ggplot(bin.packing, aes(x = empty.space, color = factor(number.runs))) + stat_ecdf()

From the ecdfs, it seems that the bulk of the distributions are

pretty similar, but off set from each other by an additive shift.

We can tell this because the curves are mostly just shifted along the

\(x\)-axis from one another, and the

overall shape is the same for each value of number.runs

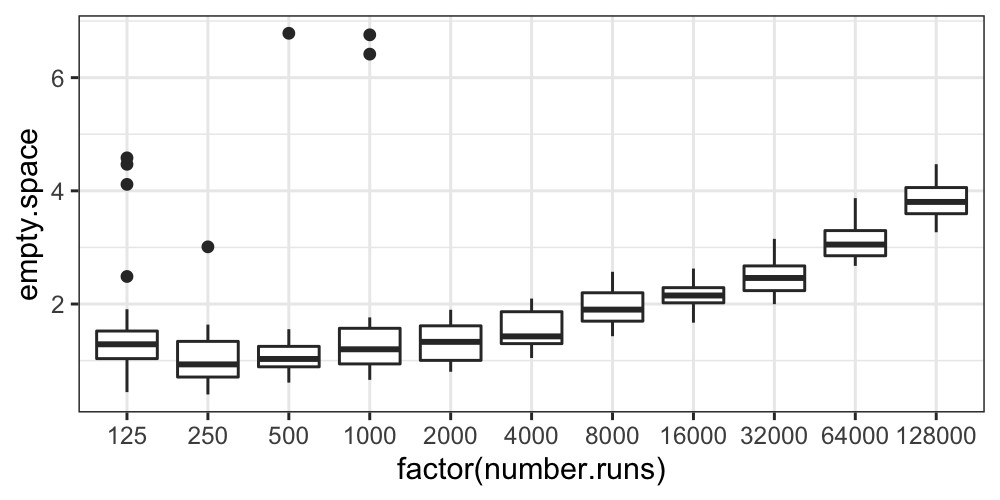

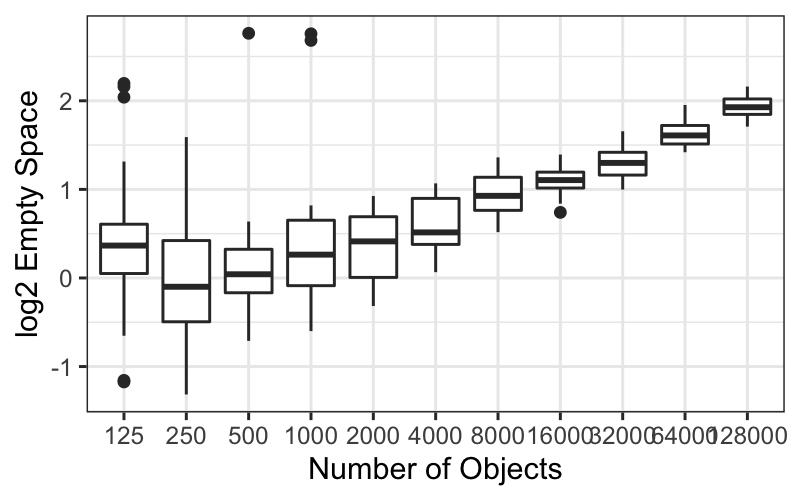

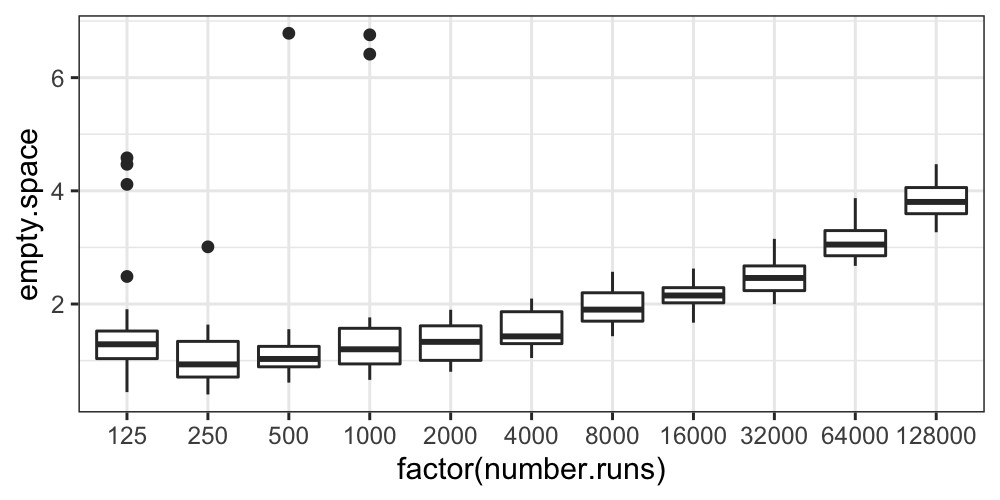

Finally, let’s draw boxplots, split by number.runs:

ggplot(bin.packing, aes(factor(number.runs), empty.space)) + geom_boxplot()

The boxplots also show us that aside from some outliers for the small

values of number.runs, the distributions at least have

similar variances.

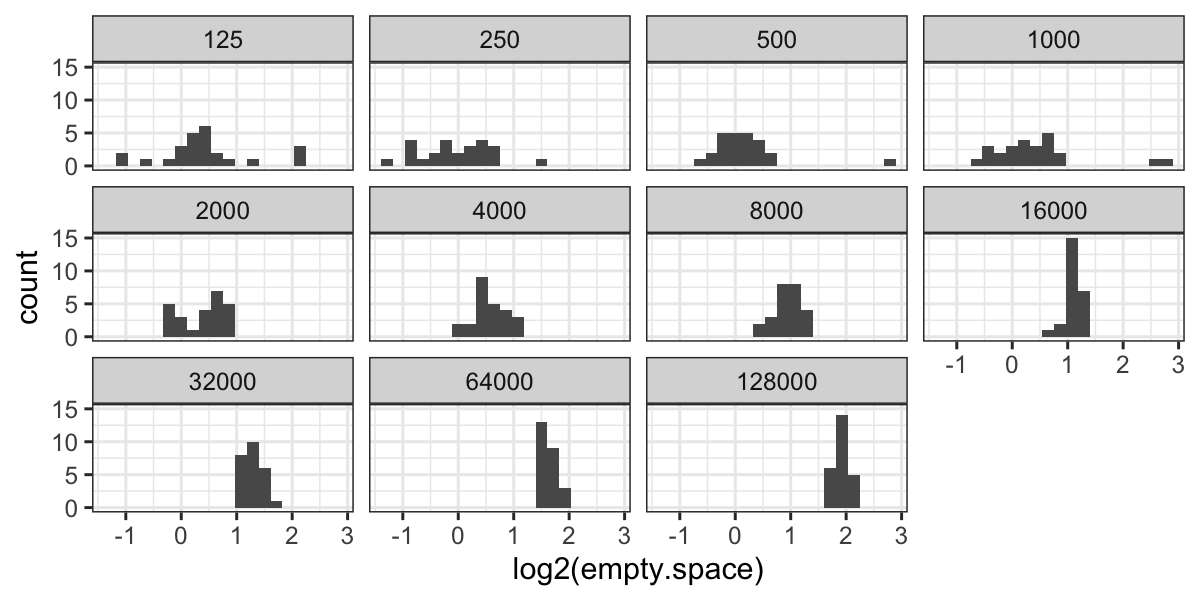

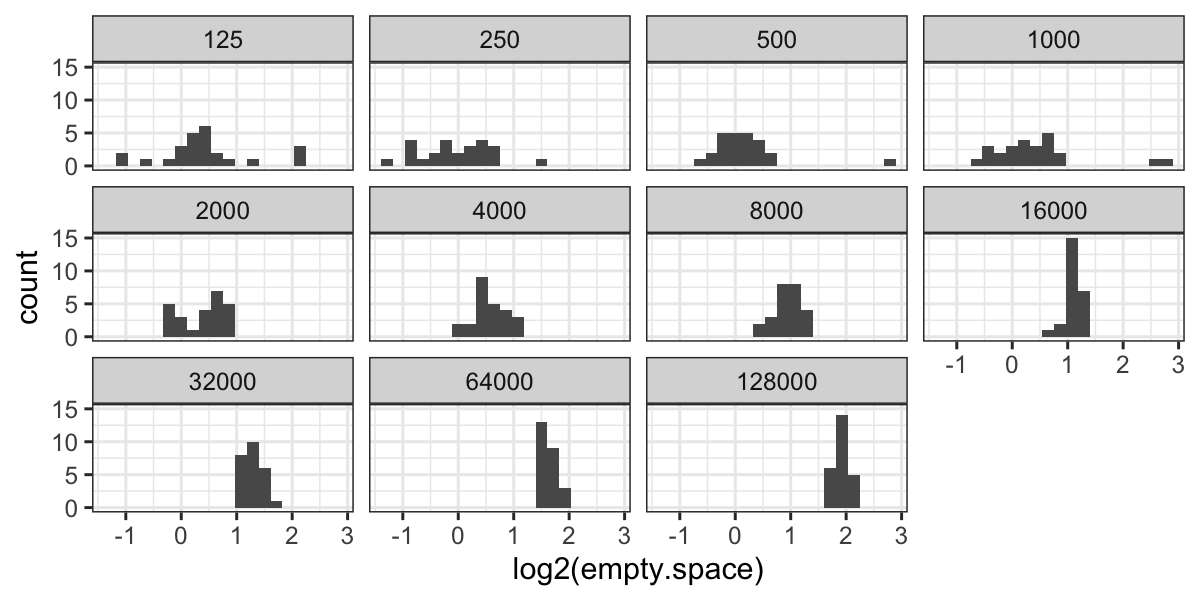

ggplot(bin.packing, aes(x = log2(empty.space))) + geom_histogram(bins = 20) +

facet_wrap(~ factor(number.runs))

Now we have outliers on both sides for 125 runs, and we have retained

the outliers for 250, 500, and 1000 runs.

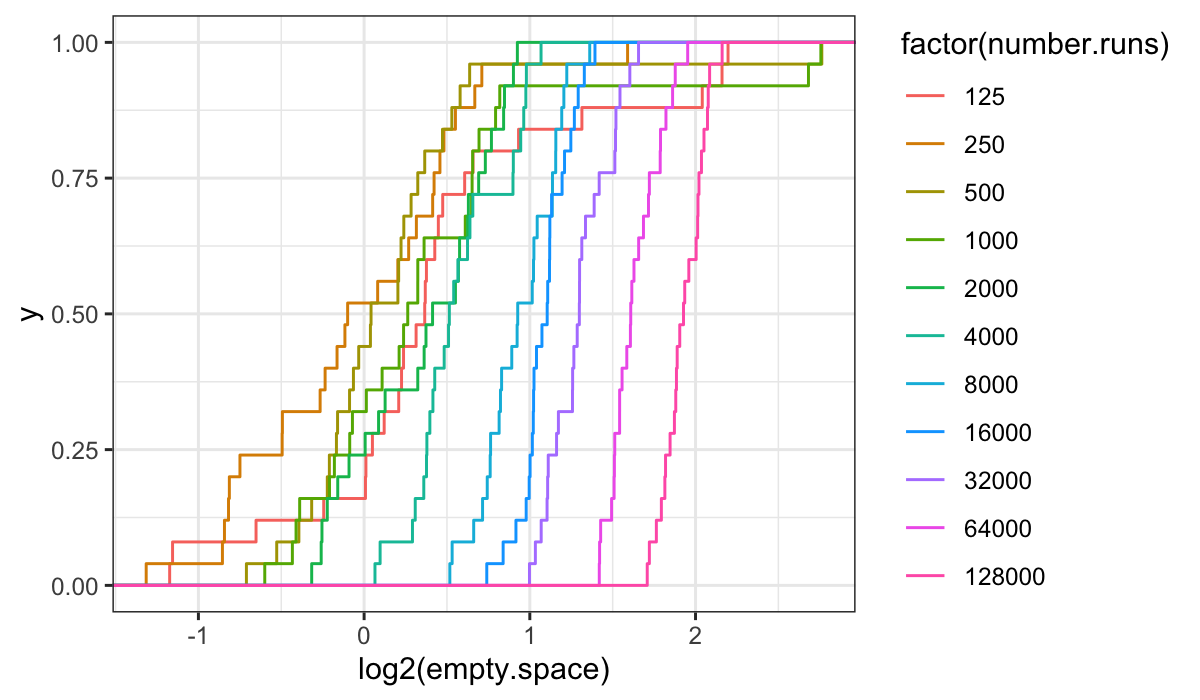

ecdfs:

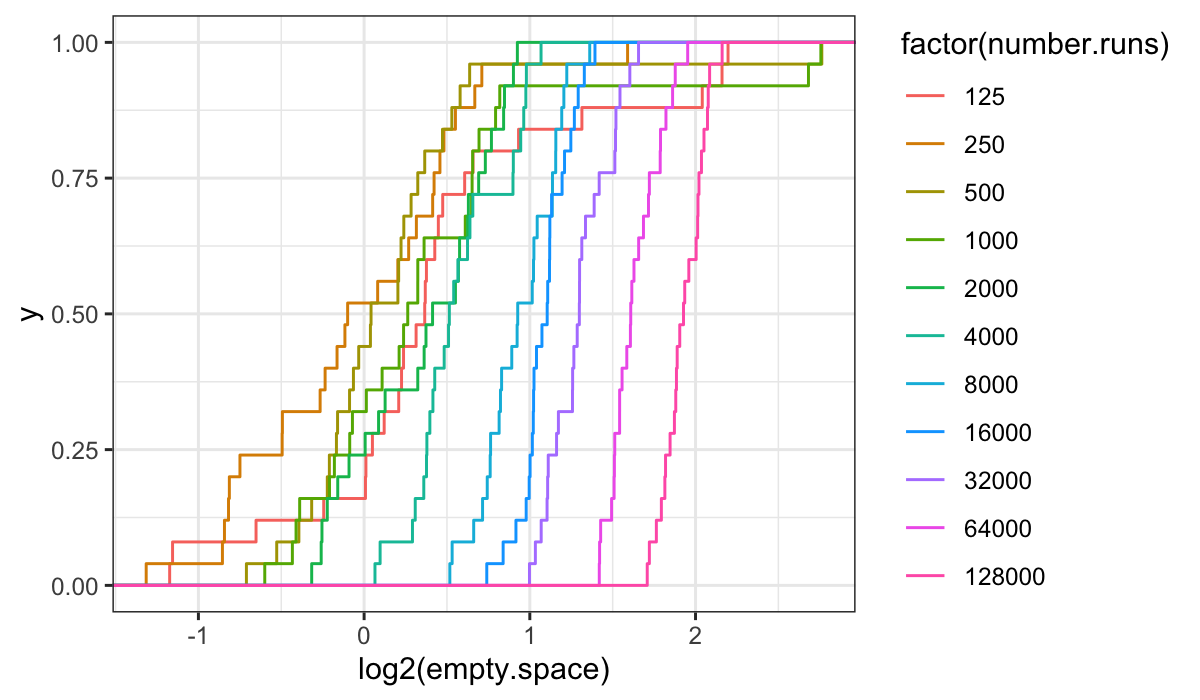

ggplot(bin.packing, aes(x = log2(empty.space), color = factor(number.runs))) + stat_ecdf()

It’s harder to get anything out of the ecdf plots on the transformed

data: we see that the variances are not the same (the slopes increase

with increasing number.runs) and that there is a location

shift, but the picture is less simple than for the raw data.

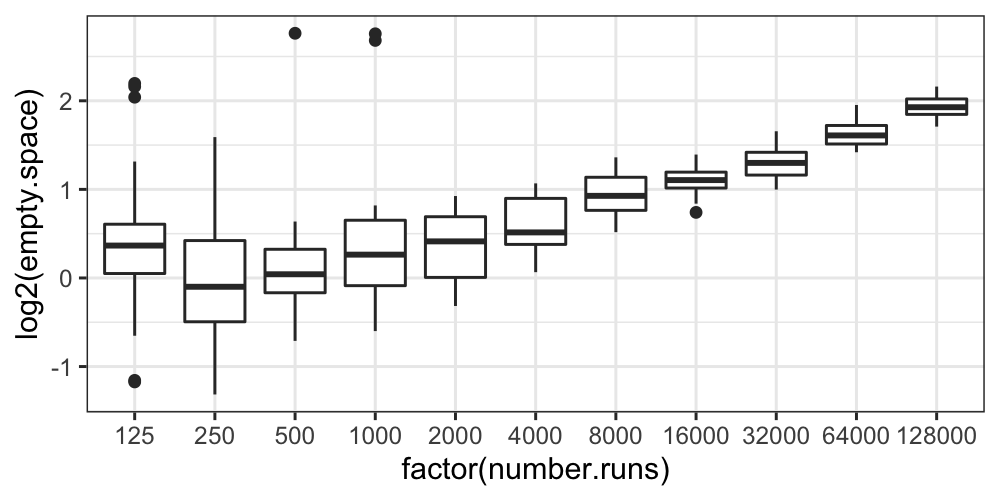

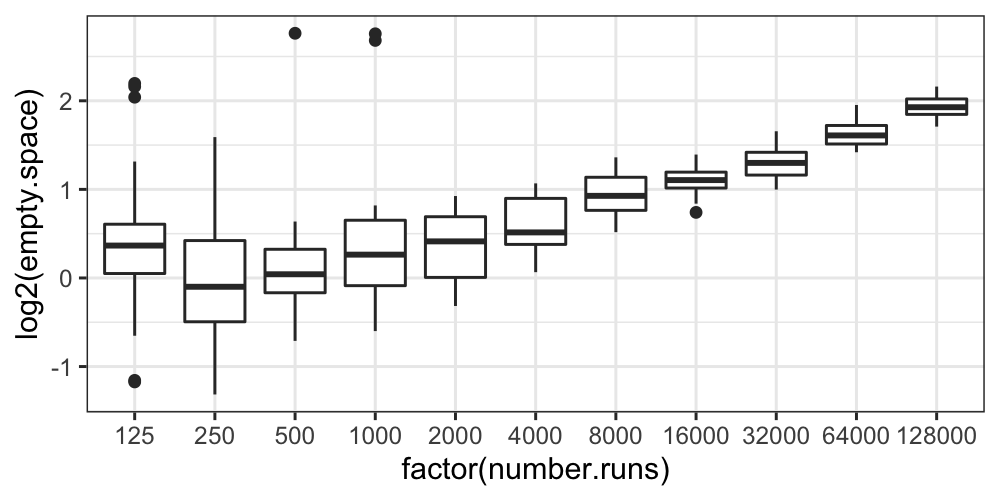

Boxplots:

ggplot(bin.packing, aes(factor(number.runs), log2(empty.space))) + geom_boxplot()

The boxplots tell essentially the same story as the histograms and

the ecdfs: the variance of the transformed data decreases with

number.runs, and we still have some outliers.

It seems that the transformation isn’t helping us at all: it’s

complicated the story about empty space and number.runs by introducing

heteroscedasticity, it hasn’t gotten rid of skewness or outliers, and it

has made the distributions more difficult to compare.

The moral here is that you should try things out that might not work,

and if you check and they don’t seem like they’re helping you should

feel free to abandon them.

We’ll do the remaining analysis on the raw values.

The next question is about the shape of the distributions: we know

there are outliers, but do the observations in the bulk of the data look

approximately normal?

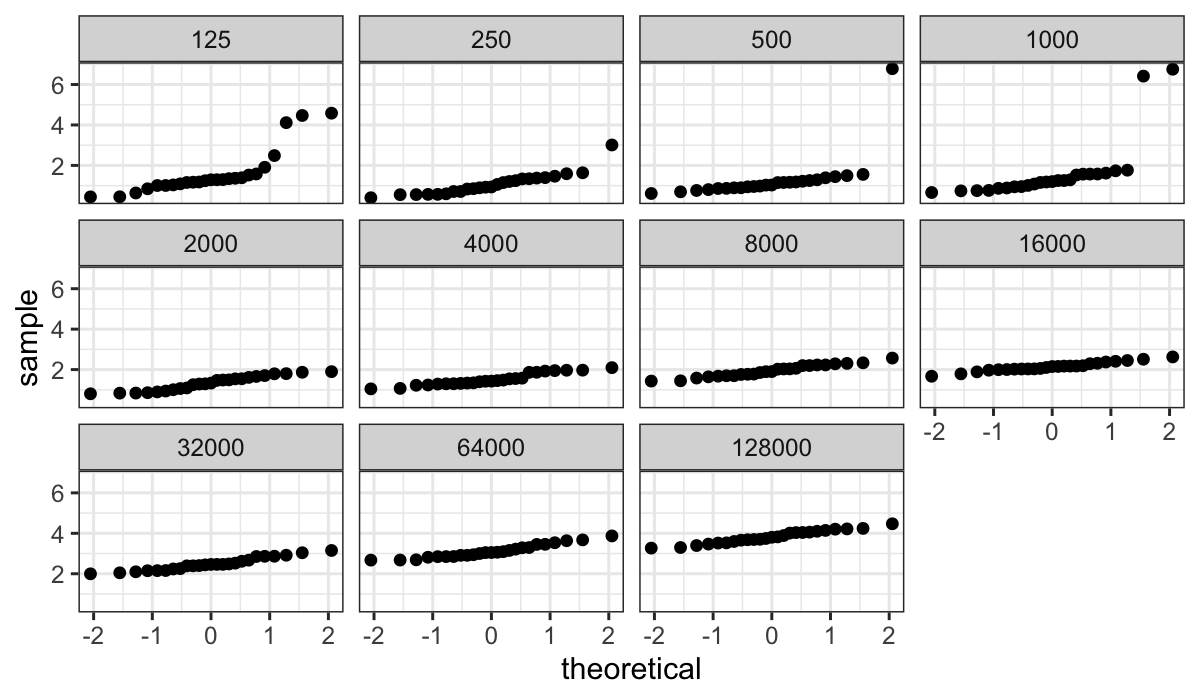

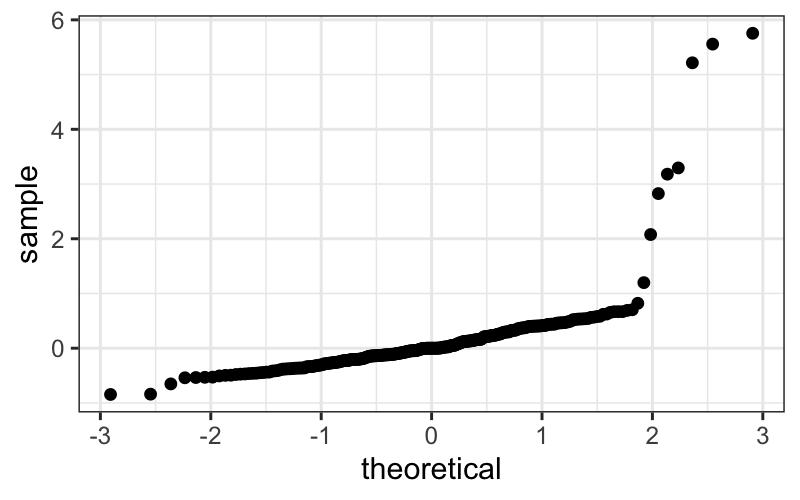

We use normal QQ plots to investigate:

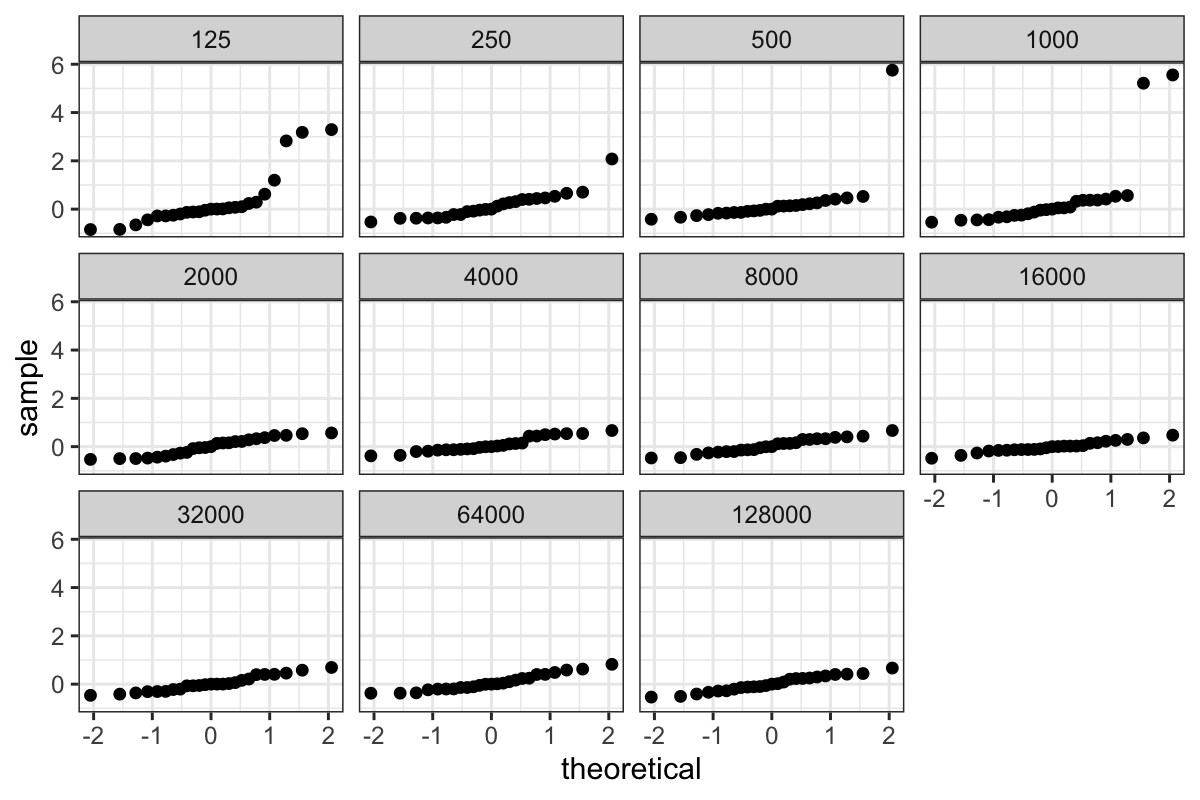

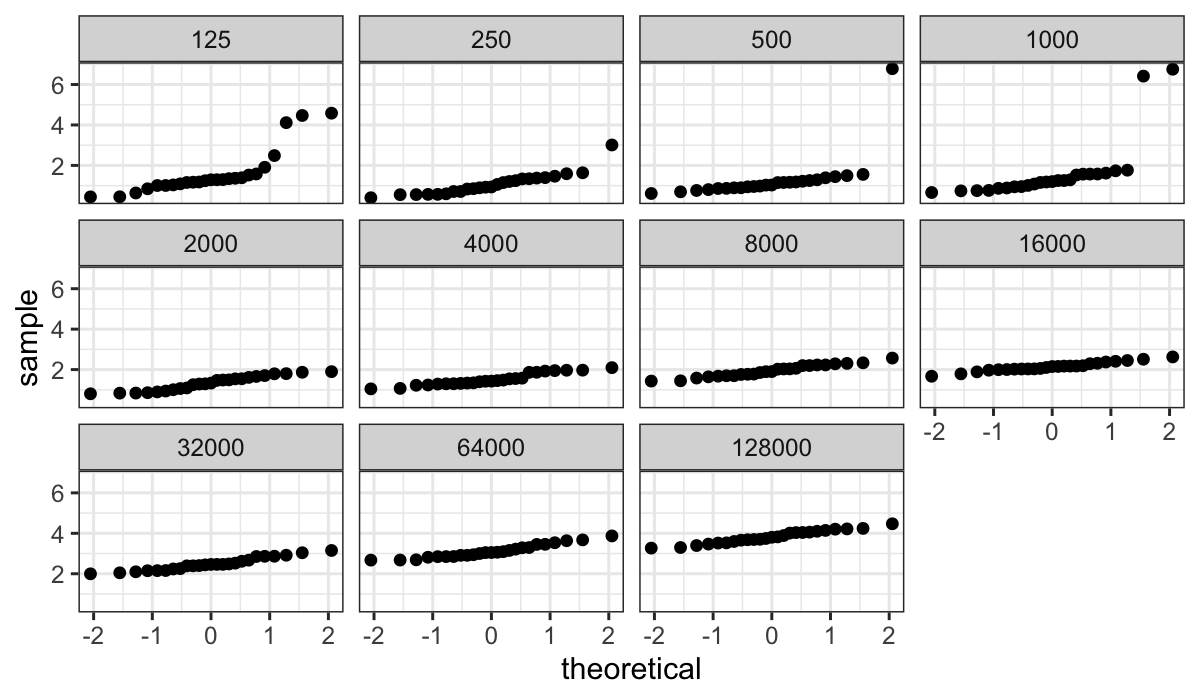

ggplot(bin.packing, aes(sample = empty.space)) +

stat_qq() + facet_wrap(~ number.runs)

The plot above shows very clearly the non-normality in log(empty

space) for smaller numbers of runs, but since the standard deviation

(slope in the QQ plot) is much smaller for the large number of runs it’s

hard to assess how straight the lines are.

We can fix this by using the argument scales = "free_y"

in the faceting function: this gives every facet its own scale on the

y-axis, spreading out the points so that we can look for linearity or

lack thereof.

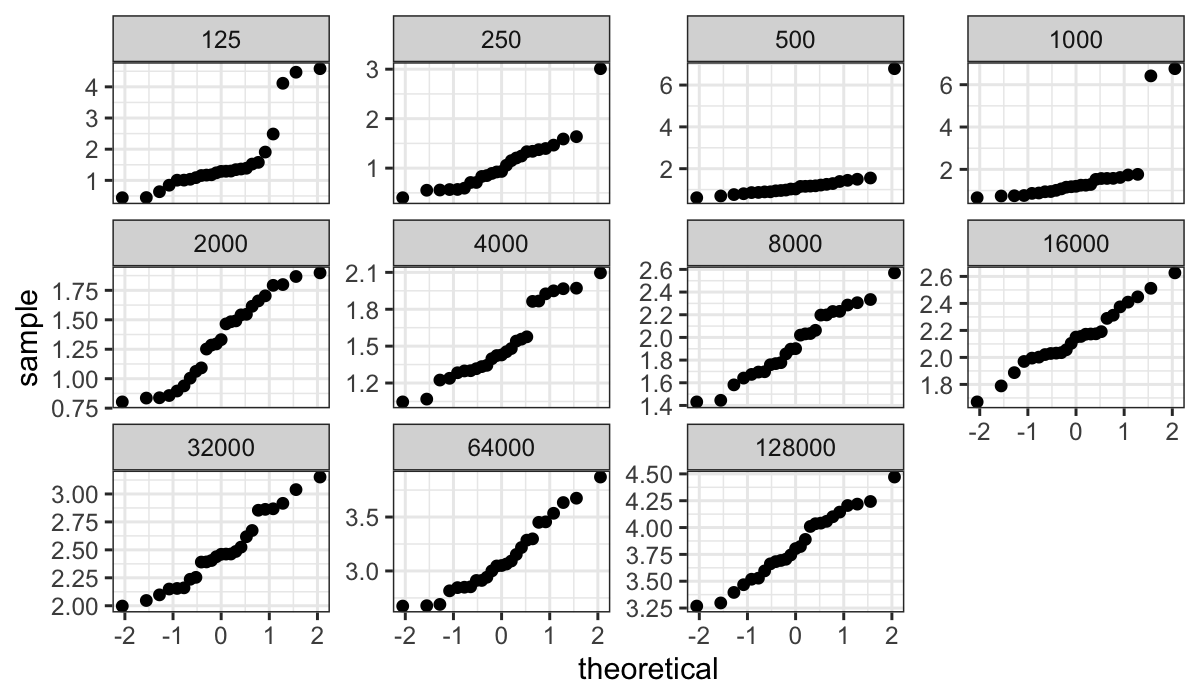

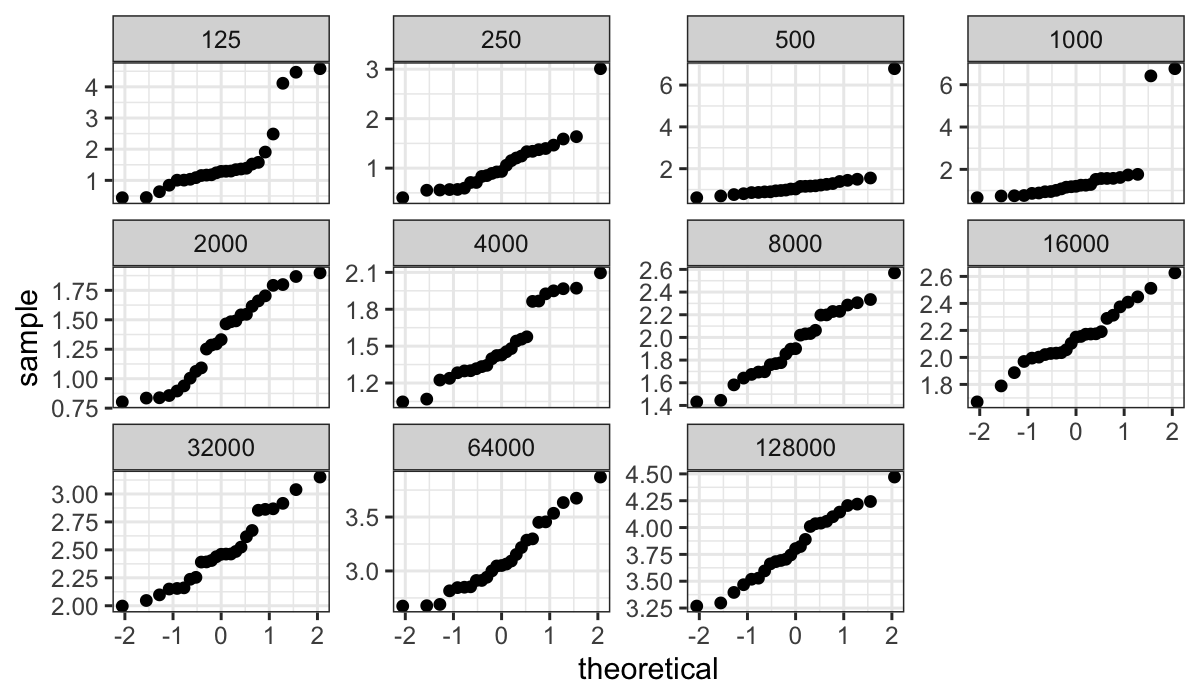

ggplot(bin.packing, aes(sample=empty.space)) +

stat_qq() + facet_wrap(~number.runs, scales = "free_y")

Question: Why just use “free_y” and not “free” (every facet gets its

own scale on both the x- and y-axis)?

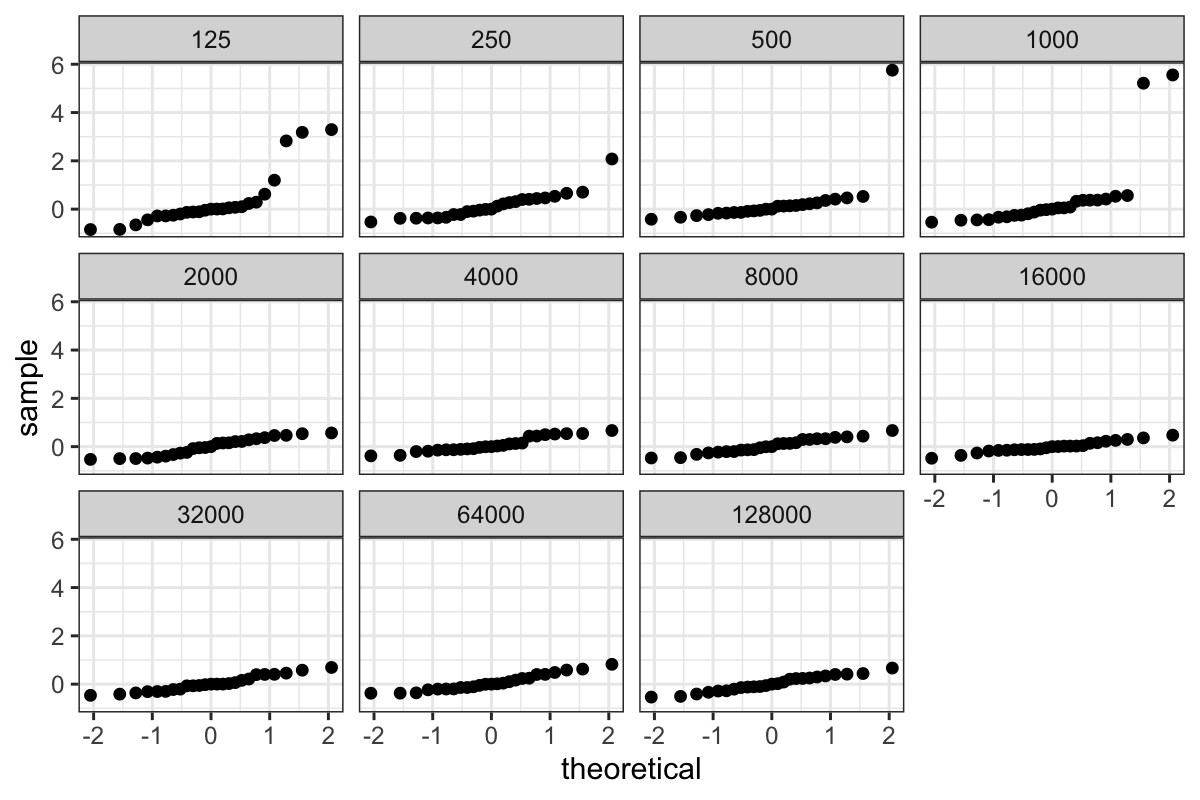

For large numbers of runs, the QQ plots are well-fitted by straight

lines. However for smallest numbers of runs there are difficulties –

especially for less than 1000 runs, where there are major outliers.

Because of the outliers, we might prefer to both build our model and

explore our residuals in a more robust way. The median is more

outlier-resistant than the mean, so we’ll use those as our fitted

values.

In Cleveland’s notation: Let \(b_{in}\) be the \(i\)th log empty space measurement for the

bin packing run with \(n\) weights. Let

\(l_n\) be the medians. The fitted

values are

\[

\hat{b}_{in} = l_n

\]

and the residuals are

\[

\hat{\varepsilon}_{in} = b_{in} - \hat{b}_{in}

\]

Let \(s_n\) be the median absolute

deviations or MADs: that is, for each \(n\), the median of the absolute value of

the residuals.

The mad() function in R gives the median absolute

deviations (multiplied by a constant 1/qnorm(3/4)=1.483 to

put the estimate on the same scale as the standard deviation.)

Let’s compute the medians and MADs:

bin_packing_summaries =

bin.packing %>%

group_by(number.runs) %>%

summarise(med = median(empty.space),

mad = mad(empty.space))

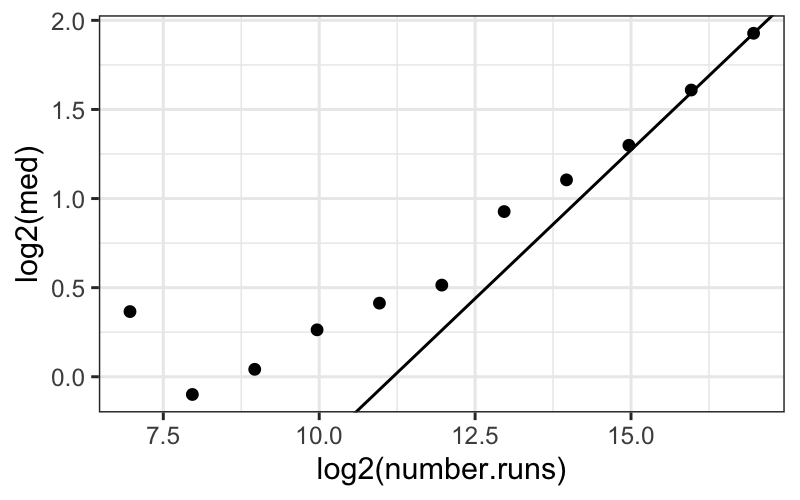

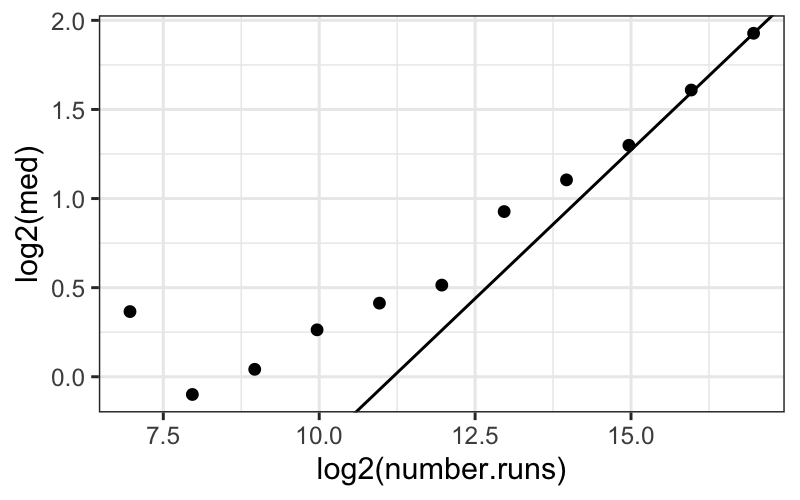

Dependence of empty space on number of runs

Theory apparently suggests that on a log-log scale, then as the

number of runs gets large, empty space approaches a linear function of

number of runs with slope \(1/3\). We

plot the median log empty space for each number of runs, plus a line

with slope 1/3 going through the last point:

## Set up the line going through the last point

slope = 1/3

intercept = max(log2(bin_packing_summaries$med)) -

max(log2(bin_packing_summaries$number.runs)) * slope

## Plot the medians plus our line

ggplot(bin_packing_summaries) +

geom_point(aes(x = log2(number.runs), y = log2(med))) +

geom_abline(aes(intercept = intercept, slope = slope))

The line does eventually provide a good fit, which is consistent (in

a very weak way) with the assertion that the line should fit when the

number of runs gets very large.

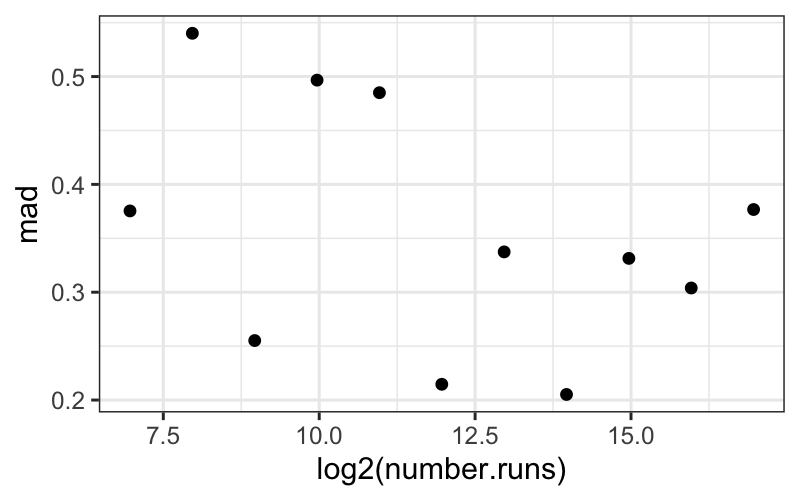

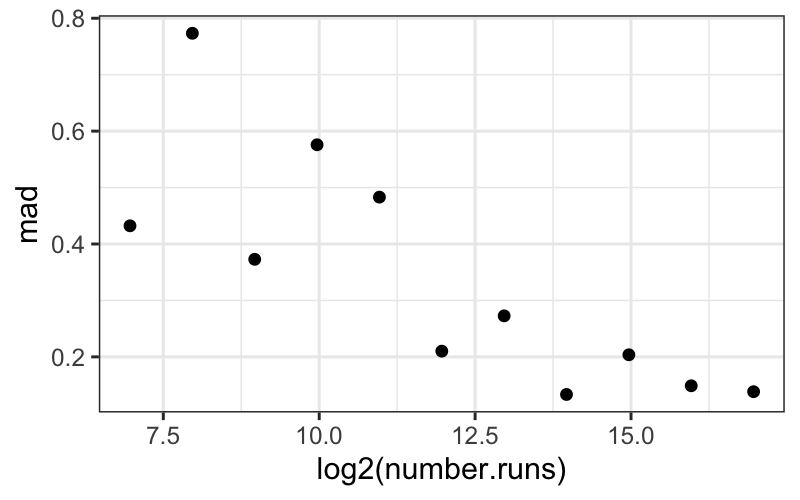

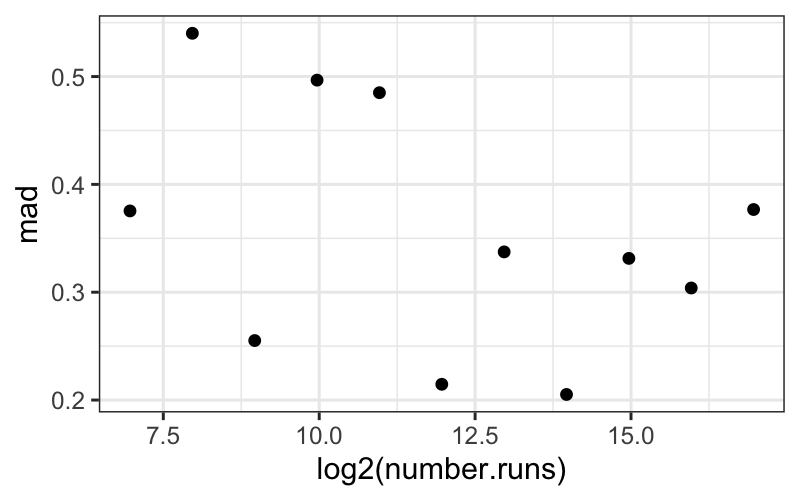

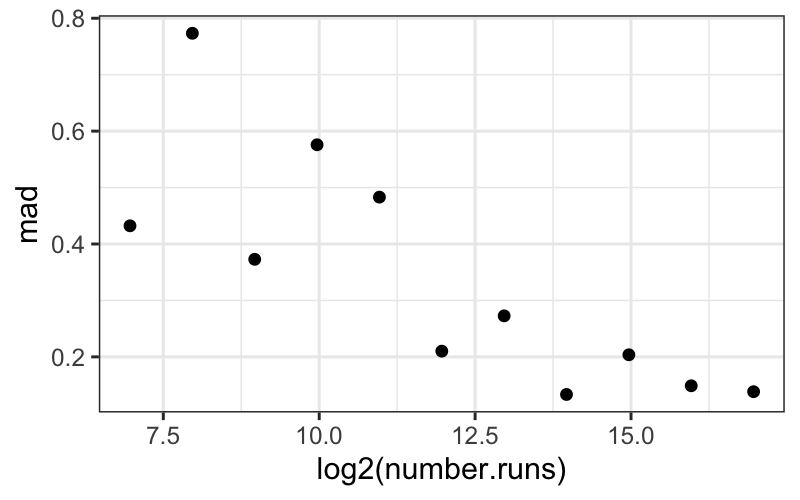

Dependence of the spread of empty space on number of runs

We can also investigate the dependence of the spreads on the number

of runs using MADs:

ggplot(bin_packing_summaries) +

geom_point(aes(x = log2(number.runs), y = mad))

Based on this plot, it doesn’t look like there’s a systematic

dependence of the spread, as measured by MAD, on number of runs.

Interpretational point: Both the MAD and the SD are legitimate

measures of spread here. The MAD measures the spread of the “bulk” of

the data, while the SD measures the spread of everything, including the

outlying points.

Here the SD decreases with number.runs (you can try

plotting it yourself) because of the outliers for small values of

number.runs. Since this is data from a simulation, these

“outliers” are real, good data points. They are not corrupt or bad, and

they need to be accounted for.

Both points, that the bulk of the data have the same spread across

different numbers of runs, and that there seem to be outliers only for

small numbers of runs, are important features of this dataset.

Examining the residuals

First let’s compute the residuals. Remember that since we’re using a

robust fit (the median as a measure of center), the residuals will be

the observed values minus the median values.

The easiest way is to use mutate on a grouped

dataframe:

bin_packing_residuals = bin.packing %>%

group_by(number.runs) %>%

mutate(residuals = empty.space - median(empty.space))

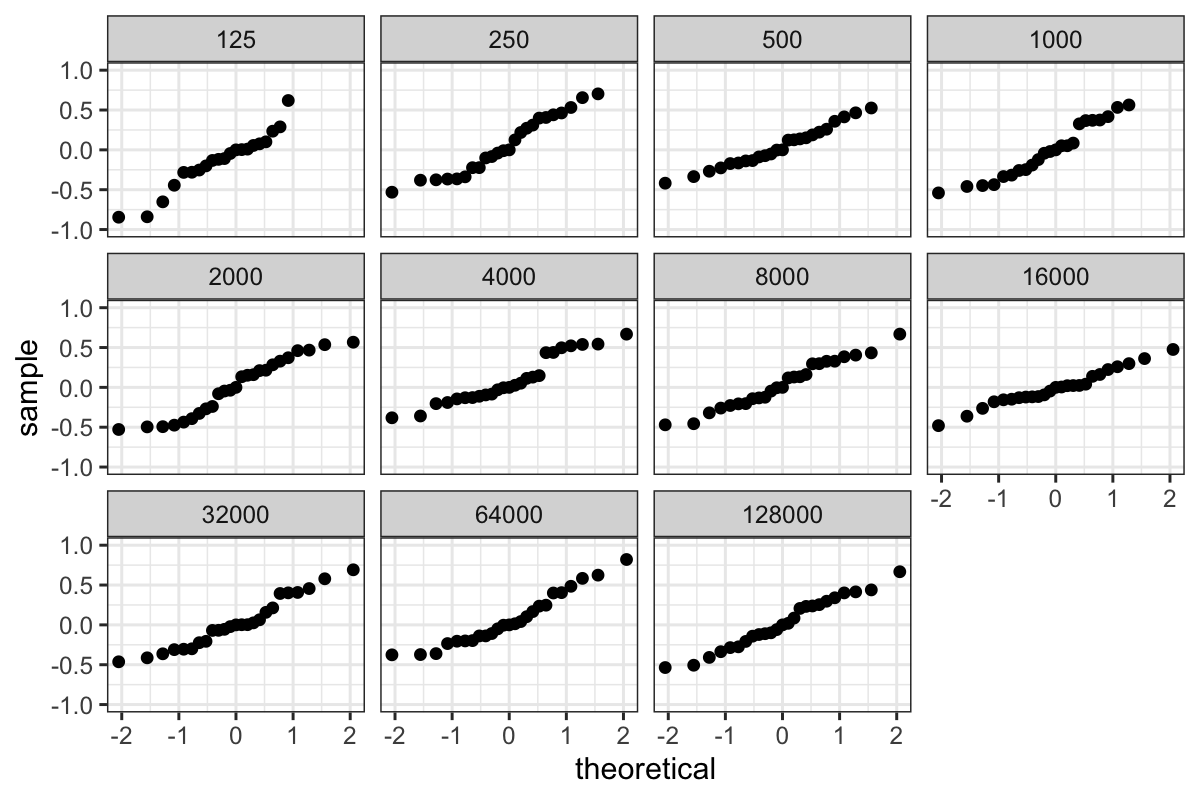

QQ plots of the residuals

Then we can plot both the pooled residuals and the residuals for each

group:

ggplot(bin_packing_residuals) + stat_qq(aes(sample = residuals)) + facet_wrap(~ number.runs)

ggplot(bin_packing_residuals) + stat_qq(aes(sample = residuals)) + facet_wrap(~ number.runs) + ylim(c(-1, 1))

## Warning: Removed 8 rows containing missing values (`geom_point()`).

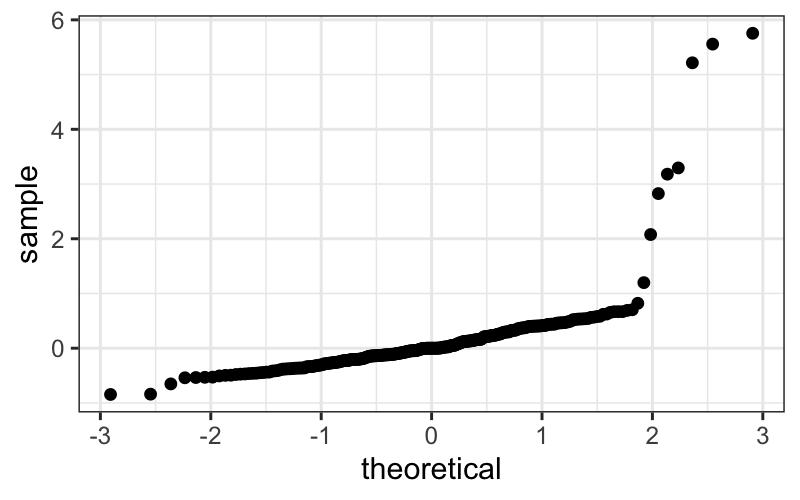

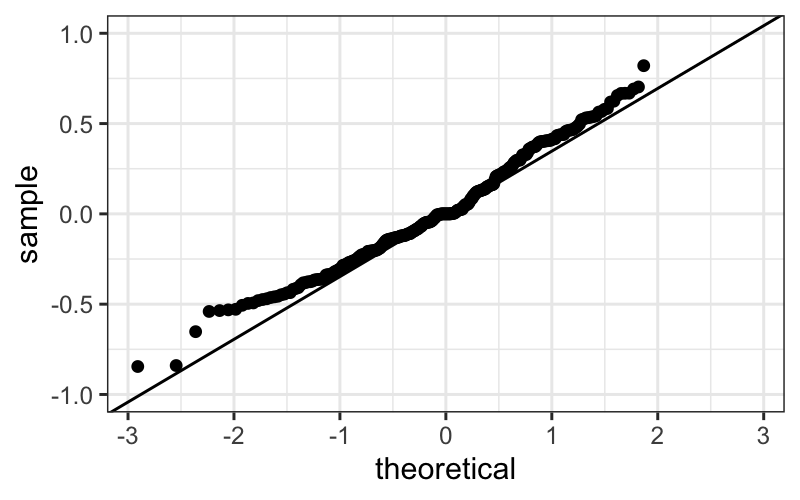

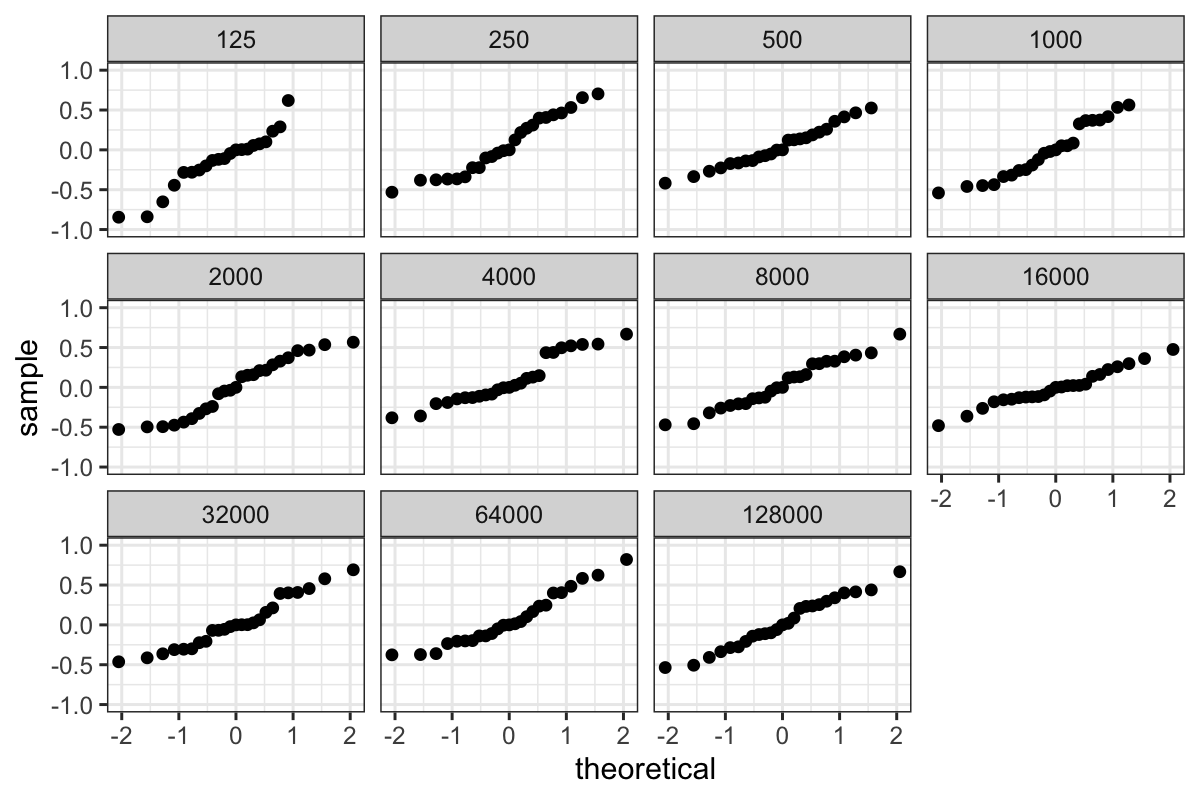

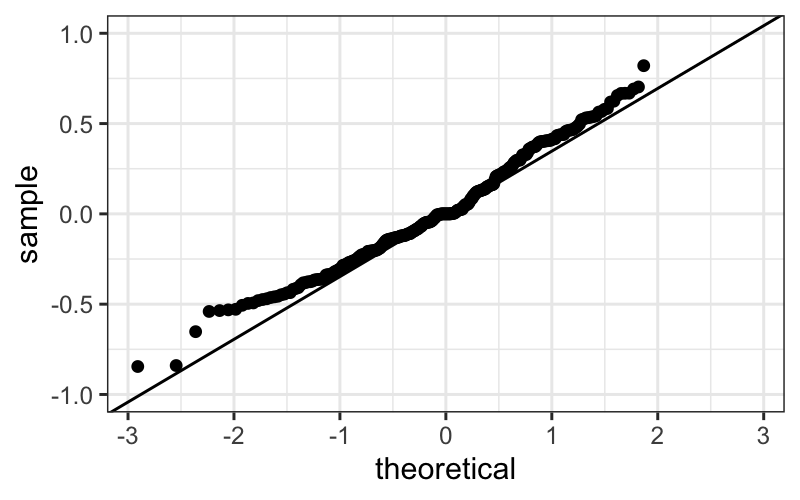

QQ plots of pooled residuals

ggplot(bin_packing_residuals) + stat_qq(aes(sample = residuals))

ggplot(bin_packing_residuals) +

stat_qq(aes(sample = residuals)) +

geom_abline(aes(intercept = 0, slope = mad(residuals))) +

ylim(c(-1, 1))

## Warning: Removed 8 rows containing missing values (`geom_point()`).

We of course have the outliers, and we see that the bulk of the

residuals are slightly leptokurtic compared to a normal

distribution.

We can see this more systematically by computing MADs and plotting

them against empty space:

bin_packing_summaries_log2 =

bin.packing %>%

group_by(number.runs) %>%

summarise(med = median(log2(empty.space)),

mad = mad(log2(empty.space)))

ggplot(bin_packing_summaries_log2) + geom_point(aes(x = log2(number.runs), y = mad))

From this plot, we see that the mads decrease pretty much linearly

with number.runs.

Because we started out by looking at the un-transformed data, we know

that this heteroscedasticity entirely due to the log transformation. If

we had gone through the analysis only with the log-transformed data, we

might have thought this was interesting and tried to explain why the

variance gets smaller when number.runs gets larger.

This would probably lead us down the wrong path though, and it is

more informative to think about the simulations as having the same

spread in the raw amount of empty space across all values of

number.runs.

Our model

Based on the work we’ve done so far, a model for the “bulk” of the

bin packing data (the data excluding the outliers) is

\[

b_{in} = l_n + \varepsilon_{in}

\] where

- \(b_{in}\) is the value of empty

space for the \(i\)th simulation with

\(n\) runs.

- \(l_n\) is the median value of

empty space for the simulations with \(n\) runs.

- The \(\varepsilon_{in}\) values are

independent and identically distributed.

If we were interested in testing or inference, we might feel that the

residuals look close enough to normal that we would be happy with normal

theory, or we might feel that the deviations from normal are enough to

warrant nonparametric tests.

However, the biggest issue here is the outliers: we aren’t really

going to be happy with our model until we find an explanation for

them.

What have we learned?

About the bin packing algorithm:

- This suggests that there are two regimes for the bin-packing

algorithm: one where the empty space is within a couple of MADs of the

median, and another where we have a lot more empty space than

normal.

- The second regime only seems to happen with small values of

number.runs, and if we were the people running the

simulation we would probably want to go back and look at the “outlier”

points that had much more empty space than the bulk.

- The variance in the first regime (for the bulk of the data) doesn’t

seem to change with number of runs.

About data analysis:

- Transformations don’t always work: you need to check if they’re

helping and abandon them if they’re not.

- The different measures of center and spread tell us qualitatively

different things about the data. In this case, both MADs and SDs are

valid summaries, telling us different things about the spread of the

data.

If we were the people performing the simulations, our next step would

be to figure out what’s happening with the outlying points and explain

why the variance is the same across the different values of

number.runs. The former requires more information about the

simulations. The latter you might be able to guess at, but it’s not

really the focus here.