Newton’s method

Agenda today

Newton’s method

Review method of moments

Reading:

- Kenneth Lange, Numerical Analysis for Statisticians, Section 11.2,

13.3

Newton’s method

Iterative method for finding local minimum/maximum of a

function.

Also known as Newton-Raphson, after Isaac Newton and Joseph

Raphson (Raphson published in 1690, Newton wrote a similar method in

1671 but didn’t publish until 1736)

Initial description is for finding zeros of a function

This turns out to be equivalent to an optimization

problem/finding maxima of functions, as we need.

Notation

Start off with a one-dimenisonal parameter:

\(\theta\): The parameter, a

scalar

\(\ell (\theta)\): The log

likelihood at \(\theta\).

\(\ell'(\theta)\): The first

derivative of the log likelihood at \(\theta\).

\(\ell''(\theta)\): The

second derivative of the log likelihood.

What

Our goal: Find the value of \(\theta\) that maximizes \(\ell(\theta)\).

Given that we are at a point \(\theta_n\), one Newton step is given by

\[

\theta_{n+1} = \theta_n - \ell''(\theta_n)^{-1}

\ell'(\theta_n)

\]

Newton’s method algorithm:

Start at a point \(\theta_0\)

Iterate \(\theta_{n+1} = \theta_n -

\ell''(\theta_n)^{-1} \ell'(\theta_n)\) until some

stopping criterion is reached.

Usually stop when the derivative, \(\ell'(\theta_n)\) is sufficiently close

to zero.

Why

Suppose we want to maximze a quadratic:

\[

f(\theta) = a + b \theta + c \theta^2

\]

We can solve for the maximum/minimum analytically by setting the

first derivative equal to 0:

\[

f'(\theta) = b + 2 c \theta

\]

If we want \(b + 2c \theta^\star =

0\), we take \(\theta^\star = -\frac{b

}{2c}\)

Recast this result as a “step” from \(\theta_0\) instead of a single

optimization:

We start at \(\theta_0\)

\(\theta_1\) should be \(-\frac{b}{2c}\)

We want to write \(\theta_1 = \theta_0

+ ???\)

\[

\begin{align*}

\theta_1 &= \theta_0 + (\theta_1 - \theta_0) \\

&=\theta_0 -\frac{b}{2c} - \theta_0 \\

&=\theta_0 -\frac{b + 2c \theta_0}{2c} \\

&=\theta_0 -\frac{ f'(\theta_0)}{f''(\theta_0)}

\end{align*}

\]

since \(f'(\theta_0) =

b + 2c\theta_0\) and \(f''(\theta_0) = 2c\)

Intuition for general, not-necessarily-quadratic functions:

We are not only dealing with quadratic functions, but we can

approximate smooth, differentiable functions by quadratic

functions.

Taylor approximation of \(\ell(\theta)\) around \(\theta_0\): \[

\ell(\theta) \approx \ell(\theta_0) + \ell'(\theta_0)(\theta -

\theta_0) + \frac{1}{2} \ell''(\theta_0) (\theta - \theta_0)^2

\]

A Newton step finds an extreme point for the

approximation.

Example 1: Normal mean

\[

x_1,\ldots, x_n \sim N(\theta, 1)

\]

Likelihood: \[

L(\theta) = \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2}

(x_i - \theta)^2 \right)

\]

Log likelihood: \[

\ell(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \log(2\pi)- \frac{1}{2}

(x_i - \theta)^2\right]

\]

First derivative: \[

\ell'(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \theta)

\]

Second derivative \[

\ell''(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n (-1) = -n

\]

Newton “step”:

\[

\begin{align*}

\theta_1 &= \theta_0 -\ell'(\theta_0) /

\ell''(\theta_0)\\

&= \theta_0 + \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \theta_0) / n \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^n x_i / n

\end{align*}

\]

This puts us at the maximum, as you can check by evaluating first and

second derivatives.

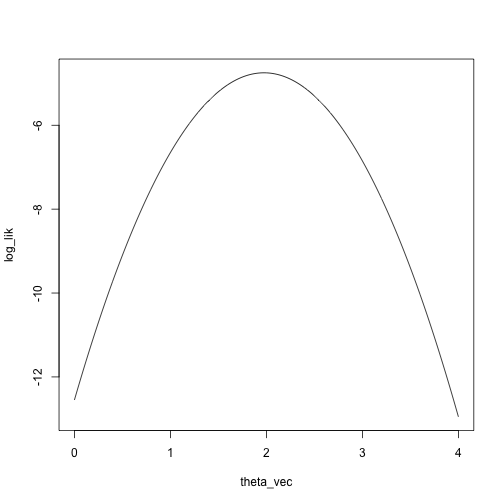

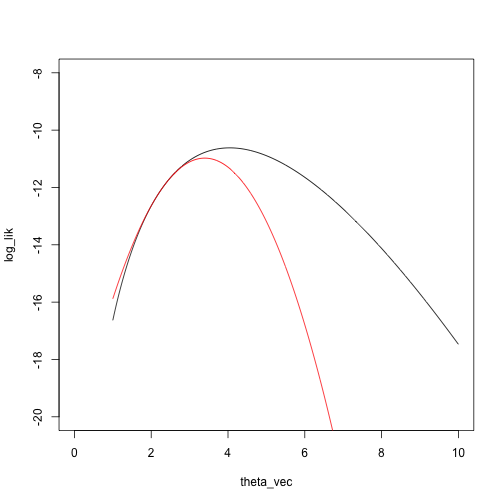

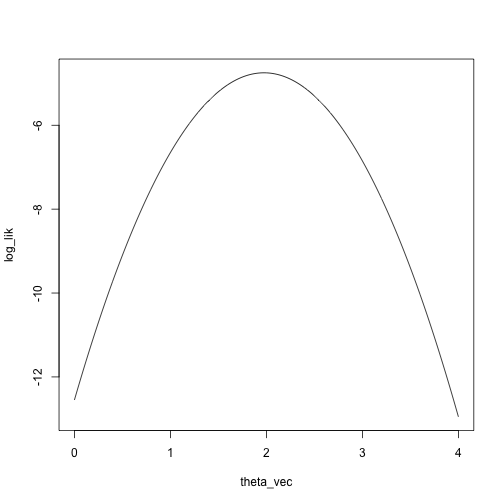

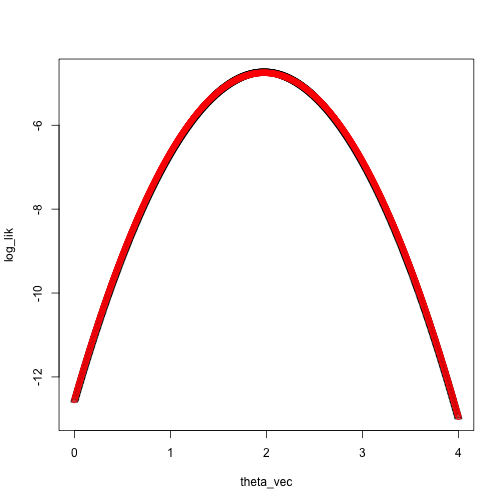

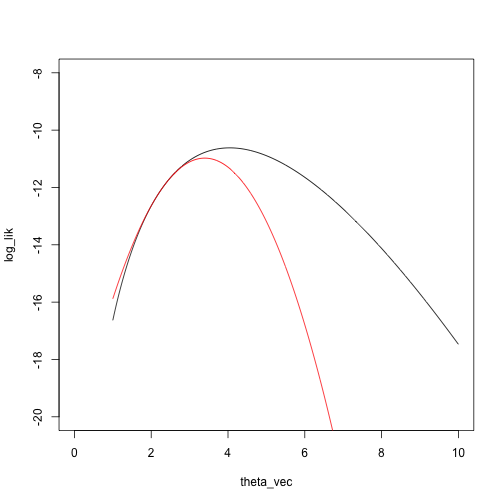

Let’s look at the log likelihood and the Taylor approximation of the

log likelihood:

x <- c(1.1, 2.3, 3, 1.5)

theta_vec <- seq(0, 4, length.out = 1000)

log_lik <- sapply(theta_vec, function(theta) sum(log(dnorm(x, mean = theta, sd = 1))))

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l')

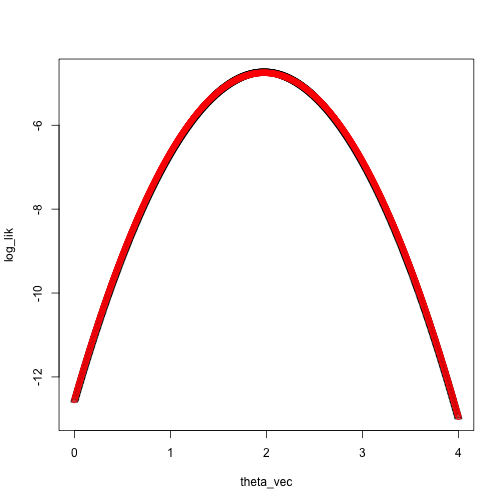

Taylor approximation:

theta_0 <- 0

taylor_approx <- function(theta, theta_0, loglik, dloglik, d2loglik, x) {

loglik(theta_0, x) + dloglik(theta_0, x) * (theta - theta_0) + .5 * d2loglik(theta_0, x) * (theta - theta_0)^2

}

loglik_norm <- function(theta, x) sum(log(dnorm(x, mean = theta, sd = 1)))

dloglik_norm <- function(theta, x) sum(x - theta)

d2loglik_norm <- function(theta, x) -length(x)

taylor_approx_vector <- sapply(theta_vec, taylor_approx, theta_0 = 0, loglik = loglik_norm, dloglik = dloglik_norm, d2loglik = d2loglik_norm, x = x)

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, pch = 2)

points(taylor_approx_vector ~ theta_vec, col = 'red')

Example 2: Negative binomial

\[

x_1,\ldots, x_n \sim NB(.5, \theta)

\]

Likelihood: \[

\begin{align*}

L(\theta) &= \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{(x_i + \theta - 1)!}{(\theta-1)!

x_i!} \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^{x_i + \theta} \\

&= \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{\Gamma(x_i + \theta)}{\Gamma(\theta)

x_i!} \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^{x_i + \theta}

\end{align*}

\]

Log likelihood: \[

\ell(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \log \Gamma(x_i + \theta) - \log(x_i!) -

\log \Gamma(\theta) + (x_i + \theta) \log(1/2)

\]

First derivative: \[

\ell'(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \psi^{(0)}(x_i + \theta)- \psi^{(0)}

(\theta) + \log(1/2)

\]

Second derivative \[

\ell''(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \psi^{(1)} (x_i + \theta) -

\psi^{(1)} (\theta)

\]

Newton step:

\[

\begin{align*}

\theta_{m+1} &= \theta_m -\ell'(\theta_m) /

\ell''(\theta_m)\\

&= \theta_m - \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n(\psi^{(0)}(x_i + \theta_m)-

\psi^{(0)} (\theta_m) + \log(1/2))}{\sum_{i=1}^n (\psi^{(1)} (x_i +

\theta_m) - \psi^{(1)} (\theta_m)) }

\end{align*}

\]

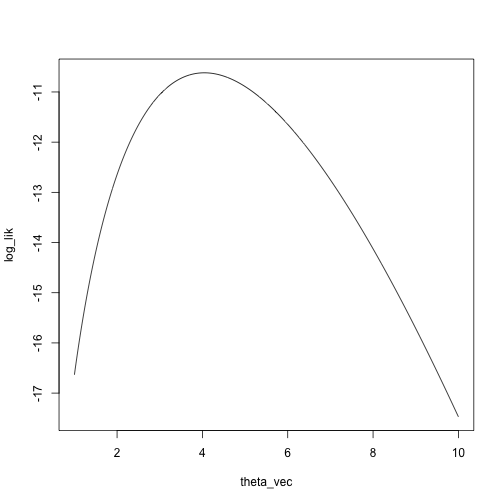

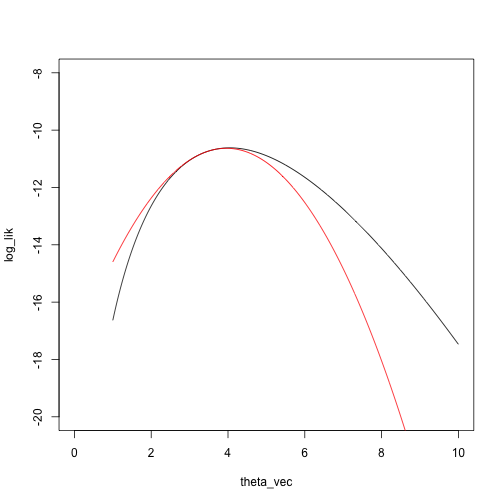

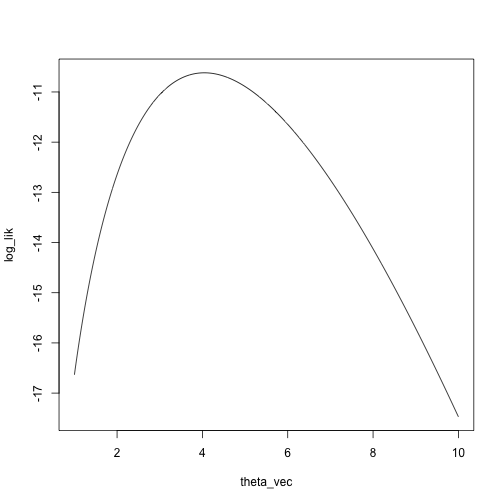

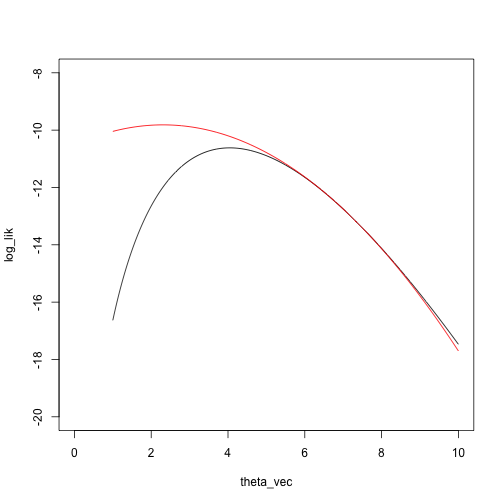

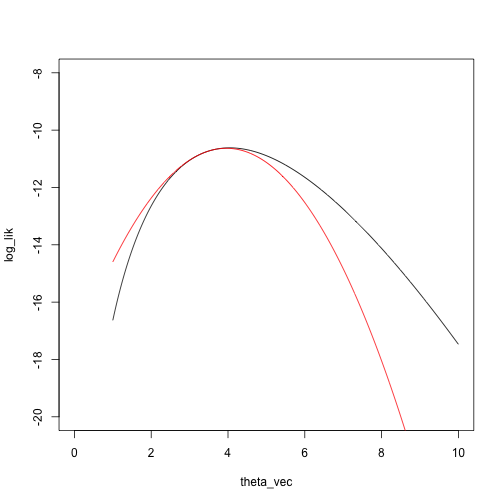

Let’s look at the log likelihood and the Taylor approximation of the

log likelihood starting at \(\theta_0 =

7\):

set.seed(0)

x <- rnbinom(n = 5, size = 4, prob = .5)

theta_vec <- seq(1, 10, length.out = 1000)

log_lik <- sapply(theta_vec, function(theta) sum(log(dnbinom(x, size = theta, prob = .5))))

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l')

loglik_nbinom <- function(theta, x) sum(log(dnbinom(x, size = theta, prob = .5)))

dloglik_nbinom <- function(theta, x) sum(digamma(x + theta) - digamma(theta) + log(.5))

d2loglik_nbinom <- function(theta, x) sum(trigamma(x + theta) - trigamma(theta))

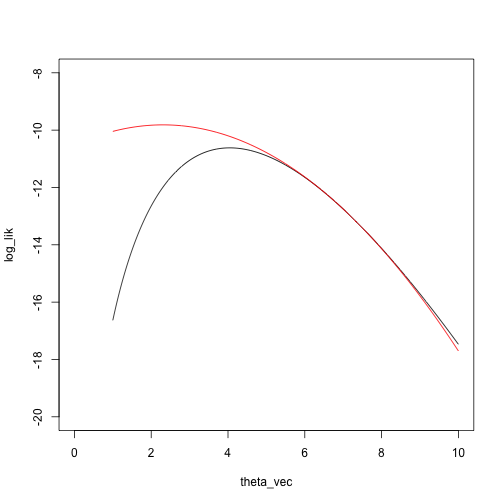

taylor_approx_vector <- sapply(theta_vec, taylor_approx, theta_0 = 7, loglik = loglik_nbinom, dloglik = dloglik_nbinom, d2loglik = d2loglik_nbinom, x = x)

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', xlim = c(0, 10), ylim = c(-20, -8))

points(taylor_approx_vector ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', col = 'red')

What is the maximizing point?

theta_vec[which.max(taylor_approx_vector)]

## [1] 2.306306

theta_0 <- 7

theta_1 <- theta_0 - dloglik_nbinom(theta_0, x) / d2loglik_nbinom(theta_0, x)

theta_1

## [1] 2.307302

taylor_approx_vector <- sapply(theta_vec, taylor_approx, theta_0 = theta_1, loglik = loglik_nbinom, dloglik = dloglik_nbinom, d2loglik = d2loglik_nbinom, x = x)

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', xlim = c(0, 10), ylim = c(-20, -8))

points(taylor_approx_vector ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', col = 'red')

Another Newton step:

theta_2 <- theta_1 - dloglik_nbinom(theta_1, x) / d2loglik_nbinom(theta_1, x)

theta_2

## [1] 3.393864

taylor_approx_vector <- sapply(theta_vec, taylor_approx, theta_0 = theta_2, loglik = loglik_nbinom, dloglik = dloglik_nbinom, d2loglik = d2loglik_nbinom, x = x)

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', xlim = c(0, 10), ylim = c(-20, -8))

points(taylor_approx_vector ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', col = 'red')

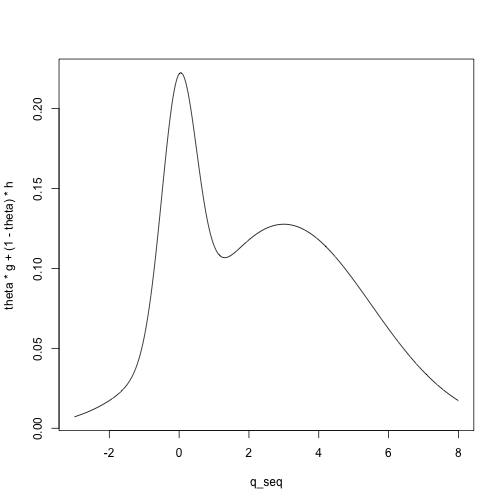

Example 3: Mixture model

Mixture model

\(x_1, \ldots, x_n\) come from a

distribution with cumulative distribution function \(\theta G + (1 - \theta)H\), where \(G\) and \(H\) are two fixed, distributions (for

example, two normal distributions with known means and variances, or two

Poisson distributions with different means).

Let \(\xi\) denote the mean of

\(G\) and \(\eta\) denote the mean of \(H\).

We want to estimate the mixing parameter \(\theta\).

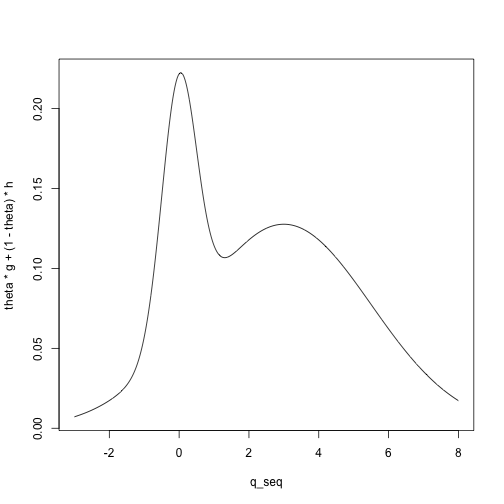

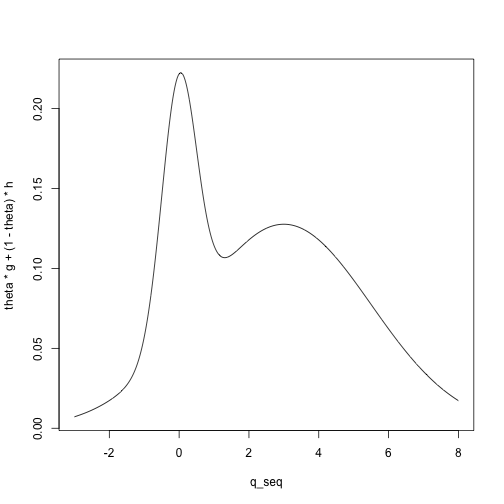

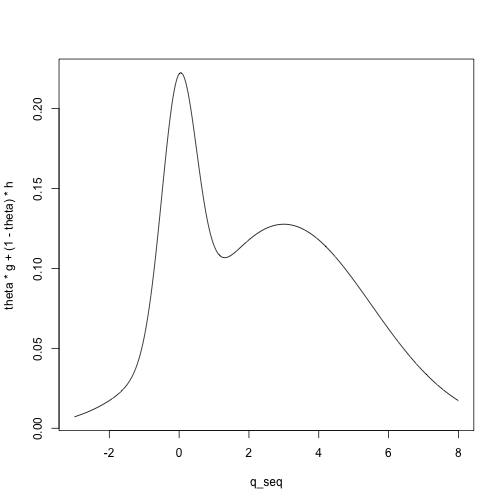

For example, we can visualize the density for a mixture of a \(N(0, .5)\) and a \(N(3, 2.5)\) distribution with mixing

parameter \(\theta = .2\):

mean_G <- 0

mean_H <- 3

sd_G <- .5

sd_H <- 2.5

q_seq <- seq(-3, 8, length.out = 1000)

g <- dnorm(q_seq, mean = mean_G, sd = sd_G)

h <- dnorm(q_seq, mean = mean_H, sd = sd_H)

theta <- .2

plot(theta * g + (1 - theta) * h ~ q_seq, type = 'l')

Let \(\phi_1(x)\) denote the density

of a \(N(0, .5)\) and \(\phi_2(x)\) denote the density of a \(N(3,2.5)\) distribution.

Then we have

\[

x_1,\ldots, x_n \sim \theta \phi_1 + (1 - \theta) \phi_2

\]

Likelihood: \[

L(\theta) = \prod_{i=1}^n (\theta \phi_1(x_i) + (1 - \theta)\phi_2(x_i))

\]

Log likelihood: \[

\ell(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \log(\theta \phi_1(x_i) + (1 -

\theta)\phi_2(x_i))

\]

First derivative: \[

\ell'(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\phi_1(x_i) - \phi_2(x_i)}{\theta

\phi_1(x_i) + (1 - \theta) \phi_2(x_i)}

\]

Second derivative \[

\ell''(\theta) = -\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{ (\phi_1(x_i) -

\phi_2(x_i))^2}{(\theta \phi_1(x_i) + (1 - \theta) \phi_2(x_i))^2}

\]

Newton step:

\[

\begin{align*}

\theta_{m+1} &= \theta_m -\ell'(\theta_m) /

\ell''(\theta_m)\\

&= \theta_m + \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\phi_1(x_i) -

\phi_2(x_i)}{\theta_m \phi_1(x_i) + (1 - \theta_m)

\phi_2(x_i)}}{\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{ (\phi_1(x_i) -

\phi_2(x_i))^2}{(\theta_m \phi_1(x_i) + (1 - \theta_m) \phi_2(x_i))^2}}

\end{align*}

\]

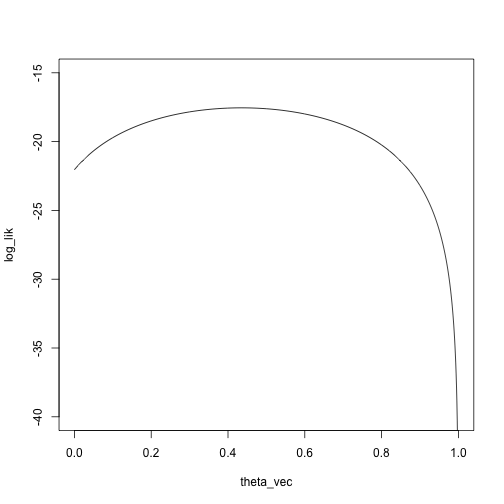

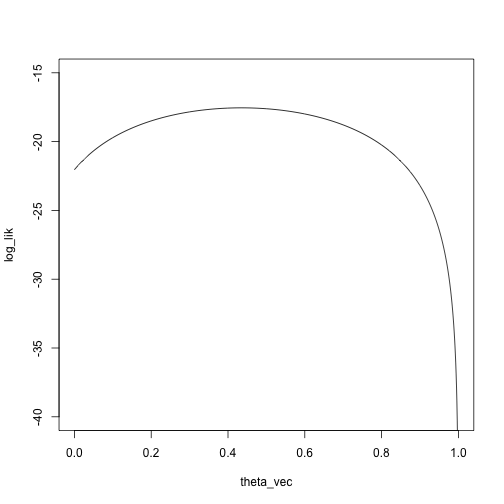

Again: log likelihood and the Taylor approximation of the log

likelihood

x <- c(-.5,.2,.2,.1,.2,3,3,4,3,4)

theta_vec <- seq(0, 1, length.out = 1000)

phi1 <- function(x) dnorm(x, mean = 0, sd = .5)

phi2 <- function(x) dnorm(x, mean = 3, sd = 2.5)

mixture_density <- function(theta, x)

theta * phi1(x) + (1 - theta) * phi2(x)

log_lik <- sapply(theta_vec, function(theta) sum(log(mixture_density(theta, x))))

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', ylim = c(-40, -15))

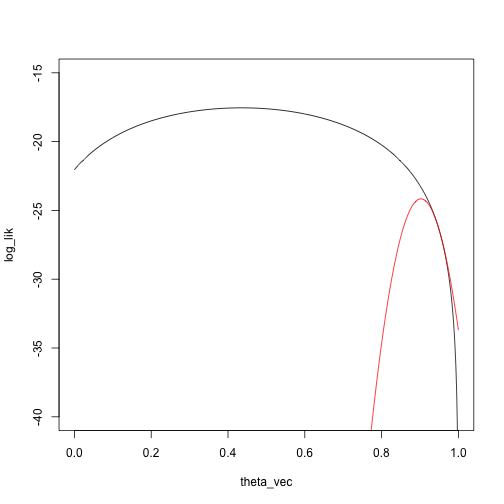

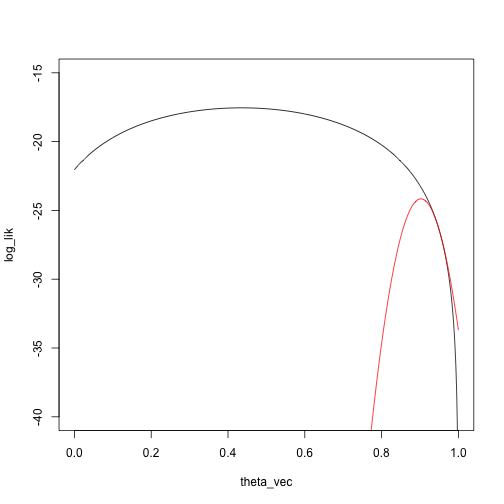

We’ll start at a pretty bad point, \(\theta_0 = .95\):

loglik_mixture <- function(theta, x)

sum(log(mixture_density(theta, x)))

dloglik_mixture <- function(theta, x)

sum((phi1(x) - phi2(x)) / (theta * phi1(x) + (1 - theta) * phi2(x)))

d2loglik_mixture <- function(theta, x)

-sum((phi1(x) - phi2(x))^2 / (theta * phi1(x) + (1 - theta) * phi2(x))^2)

taylor_approx_vector <- sapply(theta_vec, taylor_approx, theta_0 = .95, loglik = loglik_mixture, dloglik = dloglik_mixture, d2loglik = d2loglik_mixture, x = x)

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', ylim = c(-40, -15))

points(taylor_approx_vector ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', col = 'red')

What is the maximizing point?

theta_vec[which.max(taylor_approx_vector)]

## [1] 0.9029029

theta_0 <- .95

theta_1 <- theta_0 - dloglik_mixture(theta_0, x) / d2loglik_mixture(theta_0, x)

theta_1

## [1] 0.9024169

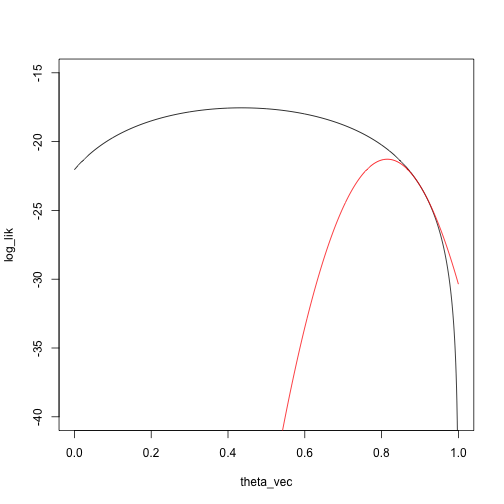

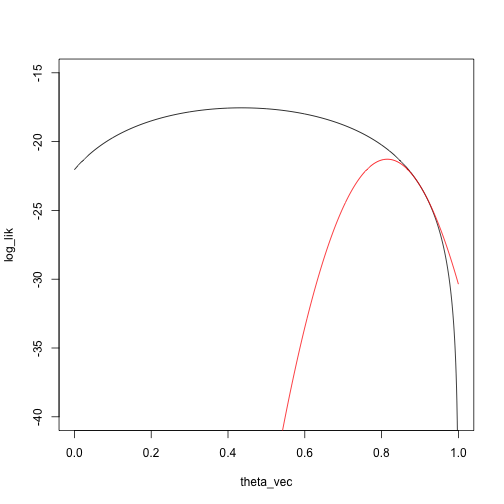

Then do a Taylor approximation around \(\theta_1\):

taylor_approx_vector <- sapply(theta_vec, taylor_approx, theta_0 = theta_1, loglik = loglik_mixture, dloglik = dloglik_mixture, d2loglik = d2loglik_mixture, x = x)

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', ylim = c(-40, -15))

points(taylor_approx_vector ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', col = 'red')

And another Newton step:

theta_2 <- theta_1 - dloglik_mixture(theta_1, x) / d2loglik_mixture(theta_1, x)

theta_2

## [1] 0.8148403

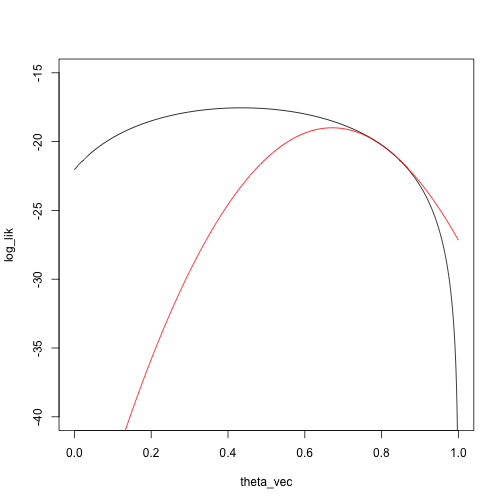

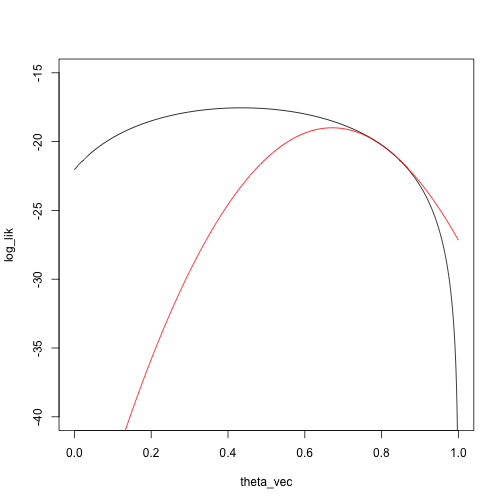

Another Taylor approximation/Newton step:

taylor_approx_vector <- sapply(theta_vec, taylor_approx, theta_0 = theta_2, loglik = loglik_mixture, dloglik = dloglik_mixture, d2loglik = d2loglik_mixture, x = x)

plot(log_lik ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', ylim = c(-40, -15))

points(taylor_approx_vector ~ theta_vec, type = 'l', col = 'red')

theta_3 <- theta_2 - dloglik_mixture(theta_2, x) / d2loglik_mixture(theta_2, x)

theta_3

## [1] 0.6714755

Potential issues

How do you choose starting values?

What if the function has no derivative/second

derivative?

What if the function has no curvature in some regions?

How do you know you will converge to a maximum and not a

minimum?

Multiple parameters: notation

Suppose we have \(p\)

paramaters.

\(\theta\): The parameters, a

vector in \(\mathbb R^p\).

\(\ell (\theta)\): The log

likelihood at \(\theta\), an element of

\(\mathbb R\).

\(d \ell(\theta)\): A vector in

\(\mathbb R^p\) of first derivatives of

the log likelihood at \(\theta\).

\(d^2 \ell(\theta)\): A matrix

in \(\mathbb R^{p\times p}\) containing

the second partial derivatives of \(\ell\).

Multiple parameters: algorithm

Our goal: Find the value of \(\theta\) that maximizes \(\ell(\theta)\).

Given that we are at a point \(\theta_n\), one Newton step is given by

\[

\theta_{n+1} = \theta_n - d^2 \ell(\theta_n)^{-1} d \ell(\theta_n)

\]

Newton’s method algorithm:

Start at a point \(\theta_0\)

Iterate \(\theta_{n+1} = \theta_n - d^2

\ell(\theta_n)^{-1} d \ell(\theta_n)\) until some stopping

criterion is reached.

Usually stop when the derivative is sufficiently close to

zero.

Same derivation and intuition as the one-parameter case: we make a

second-order Taylor approximation to the log likelihood and maximize

that.

Newton’s method for multiple parameters has the same issues as with

one parameter:

How do you choose a starting point?

What if the second derivative matrix doesn’t exist?

What if the second derivative matrix isn’t invertible?

How do you know the function converges to a maximum and not a

minimum?

In addition, we have the problem of inverting the Hessian, this

scales badly with \(p\), the number of

parameters. (Usually think of as \(O(p^3)\), but computer

scientists and computers

have worked really hard and gotten \(O(p^{2.4ish})\))

Several ways of choosing starting points, but one way that often

works is method of moments.

Method of moments

Same problem as maximum likelihood: we have a family of probability

models, indexed by a scalar or vector \(\theta\), and we need to choose one to

describe the data.

Idea:

If \(\theta\) is a \(k\)-dimensional vector (we have \(k\) parameters to estimate), derive

expressions for the first \(k\) moments

of the data, \(E_\theta(X^r)\), \(r = 1,\ldots, k\)

Compute the first \(k\)

empirical moments of the data:

\[

\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i^r, \quad r = 1,\ldots, k

\]

\(\hat \theta\) is the value of

\(\theta\) such that the empirical

moments match the theoretical moments:

\[

E_{\hat \theta}(X^r) = \sum_{i=1}^n x_i^r, \quad r = 1,\ldots, k

\]

Example: moment estimator for normal family

Our family of distributions is \(N(\mu,

\sigma^2)\), so that \(\theta = (\mu,

\sigma)\).

The first two moments are:

\(E_{\mu, \sigma}(X) =

\mu\)

\(E_{\mu, \sigma}(X^2) = \mu^2 +

\sigma^2\)

Equate the first theoretical moment to the first data moment tells us

that \(\hat \mu\) should satisfy

\[

E_{\hat \mu,\hat \sigma}(X) = \hat \mu = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i

\] and so \(\hat \mu = \frac{1}{n}

\sum_{i=1}^n x_i\)

Then equating the second theoretical moments to the second data

moment tells us that \(\hat \mu\) and

\(\hat \sigma\) should satisfy \[

E_{\mu, \sigma}(X^2) = \mu^2 + \sigma^2 = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2

\] Plugging in \(\hat \mu =

\sum_{i=1}^n x_i\) and solving gives us \[

E_{\hat \mu, \hat \sigma}(X^2) = \hat \mu^2 + \hat \sigma^2 \\

= (\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i)^2 + \hat \sigma^2\\

=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2

\] and so \(\hat \sigma^2 =

\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2 - (\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n

x_i)^2\).

If you do a little more algebra, you can see that this is a standard

estimate of the variance.

Example: moment estimator for mixture models

Mixture model

\(x_1, \ldots, x_n\) come from a

distribution with cumulative distribution function \(\theta G + (1 - \theta)H\), where \(G\) and \(H\) are two fixed, distributions (for

example, two normal distributions with known means and variances, or two

Poisson distributions with different means).

Let \(\xi\) denote the mean of

\(G\) and \(\eta\) denote the mean of \(H\).

We want to estimate the mixing parameter \(\theta\).

For example, we can visualize the density for a mixture of a \(N(0, .5)\) and a \(N(3, 2.5)\) distribution with mixing

parameter \(\theta = .2\):

mean_G <- 0

mean_H <- 3

sd_G <- .5

sd_H <- 2.5

q_seq <- seq(-3, 8, length.out = 1000)

g <- dnorm(q_seq, mean = mean_G, sd = sd_G)

h <- dnorm(q_seq, mean = mean_H, sd = sd_H)

theta <- .2

plot(theta * g + (1 - theta) * h ~ q_seq, type = 'l')

We have one parameter, so we compute the first theoretical moment:

\[

E_\theta(X) = \theta \xi + (1 - \theta) \eta

\]

Then we equate that moment to the first data moment to get our

estimate: \[

\hat \theta \xi + (1 - \hat \theta) \eta = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i

\]

\[

\hat \theta = \frac{\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i - \eta}{\xi - \eta}

\]

There isn’t anything particularly important about the first \(k\) moments, can match other aspects of the

data

We are thinking of these as starting values for maximum likelihood

estimation, but they are usually reasonable estimators in their own

right.

The idea of matching data statistics to expected values of statistics

will come up again in approximate Bayesian computation.