Merging and rebasing

Setup:

You have a branching commit history

You want to incorporate changes made in two different branches

A commit is a snapshot of the project at a certain point in time.

A branch is a pointer to a commit.

Each commit is stored as a file, containing a hash of the tree for the top-level directory, hash of the parent commit, and meta-information about the commit.

By default, a commit has as its parent the commit that HEAD was pointing to when you made the commit.

Use git checkout <branch> or

git checkout <commit hash>.

<branch> points to and HEAD change to

point to <branch> in the first case.<commit hash> and you will be in a “detached HEAD”

state in the second case. (HEAD is supposed to point to a

branch but it doesn’t here.)Setup:

You have a branching commit history

You want to incorporate changes made in two different branches

Solutions:

Merge: Make a new commit with two parents

Rebase: Applies changes from one branch onto another

Setup: We have two commits, branch1 and

branch2, and branch1 is an ancestor of

branch2.

We would like to update so that branch1 points to the

same commit as branch2.

Solution: fast-forward merge

git checkout branch1

git merge branch2What happens?

branch1 moves to point to the same commit as

branch2

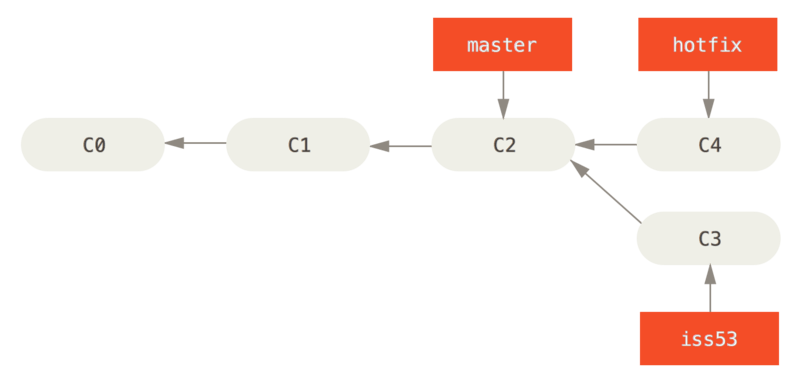

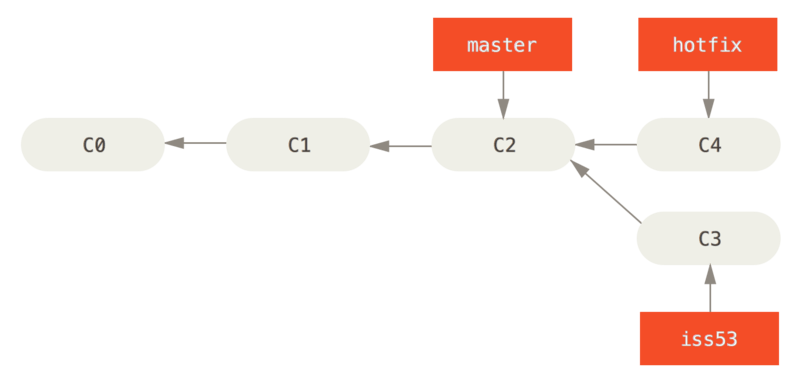

After running

$ git checkout master

$ git merge hotfix

Updating f42c576..3a0874c

Fast-forward

index.html | 2 ++

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

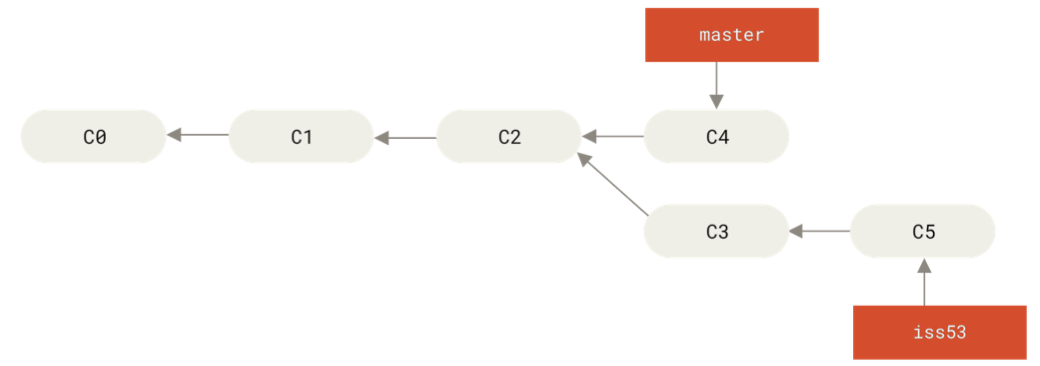

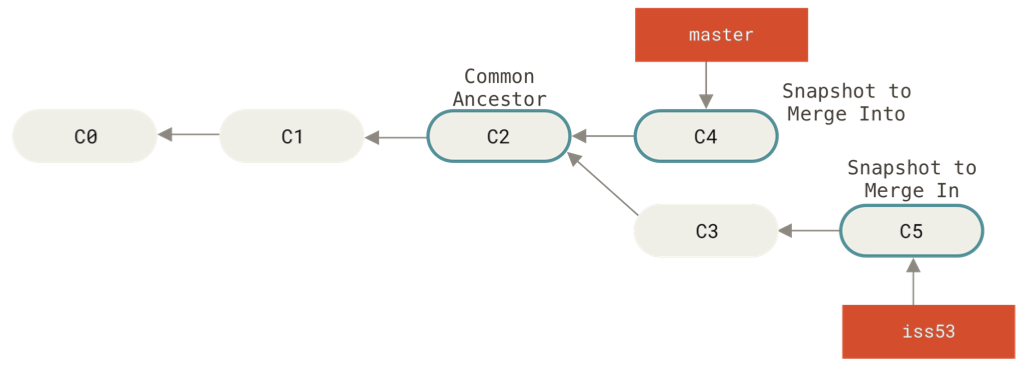

Setup: We have a diverged work history with branch1 and

branch2.

We want to integrate the changes represented by both branches.

We can merge the two branches:

git checkout branch1

git merge branch2What happens?

branch1 and

branch2branch2 and the most

recent common ancestorbranch1 to get a new commitbranch1 was pointing to and the commit that

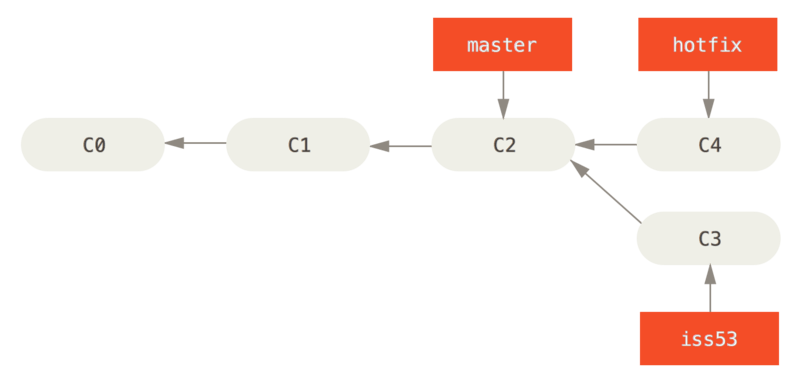

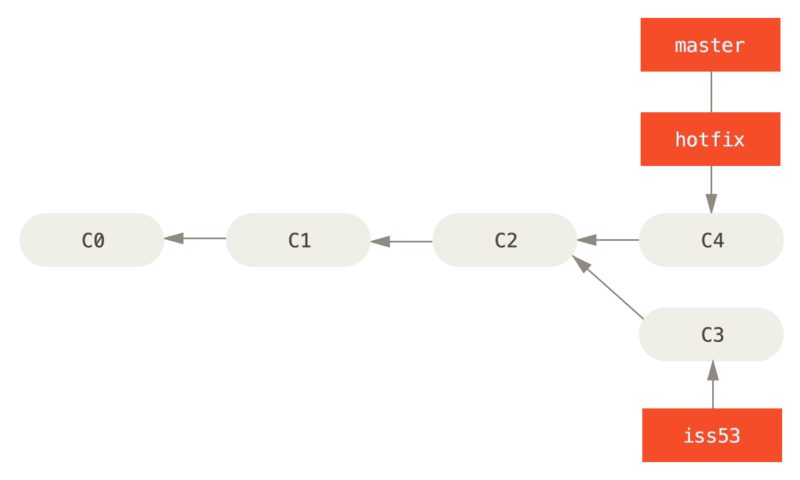

branch2 was pointing to.Starting out:

How we want the merge to look:

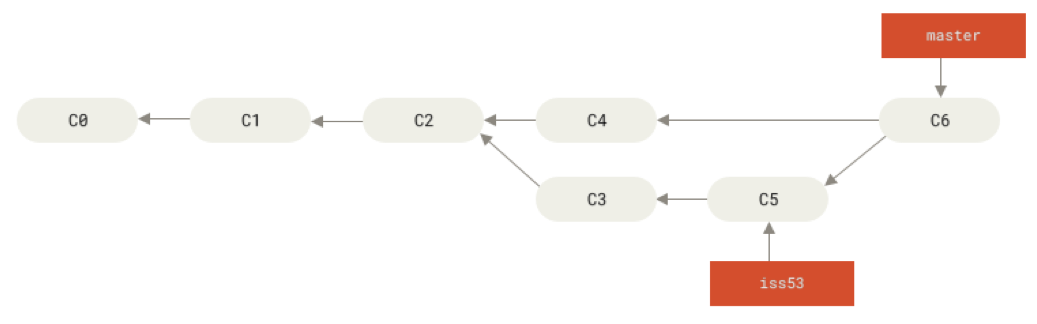

After running

git checkout master

git merge iss53

Sometimes merging doesn’t work automatically, usually because you made different changes to the same file on different branches.

If this happens, you’ll get a message telling you that the merge can’t be performed automatically:

$ git merge iss53

Auto-merging index.html

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in index.html

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.If you run git status, you get instructions about what

to do:

$ git status

On branch master

You have unmerged paths.

(fix conflicts and run "git commit")

Unmerged paths:

(use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution)

both modified: index.html

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")In this case, the file index.html will contain a section

that looks like this:

<<<<<<< HEAD:index.html

<div id="footer">contact : email.support@github.com</div>

=======

<div id="footer">

please contact us at support@github.com

</div>

>>>>>>> iss53:index.htmlThe version in HEAD is in the first section (between

<<< and ===), and the version in

iss53 is in the second section (between ===

and >>>).

Git doesn’t know which changes you want in the final merge, so you have to choose which one to keep (or do something else entirely).

Resolving the conflict:

Edit the file(s) with the merge conflicts.

Run git add on those files.

Run git commit to make the merge commit.

After fixing merge conflicts and running

git add index.html:

$ git status

On branch master

All conflicts fixed but you are still merging.

(use "git commit" to conclude merge)

Changes to be committed:

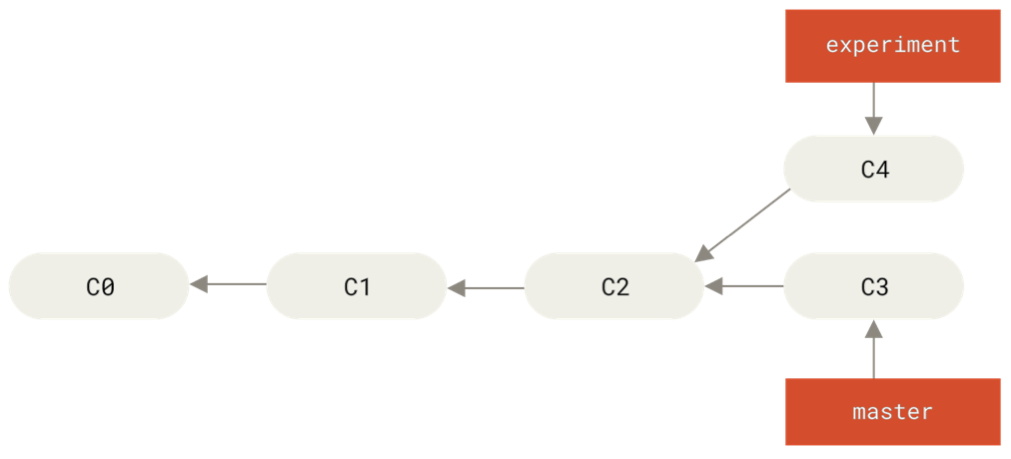

modified: index.htmlSetup: We have a diverged work history with branch1 and

branch2.

We want to integrate the changes represented by both branches.

One solution is rebasing branch2 onto

branch1:

git checkout branch2

git rebase branch1What happens?

Find the most recent common ancestor of branch1 and

branch2

Find all the differences between branch2 and the

most recent common ancestor

Apply those changes to branch1 to get the new

commit

Same result as what we would get from a merge commit, but the history is different.

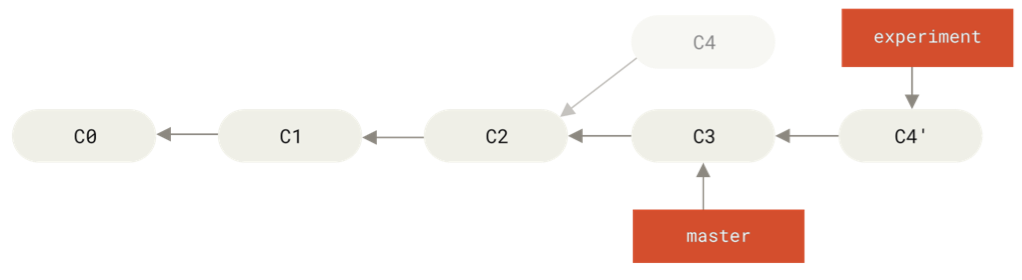

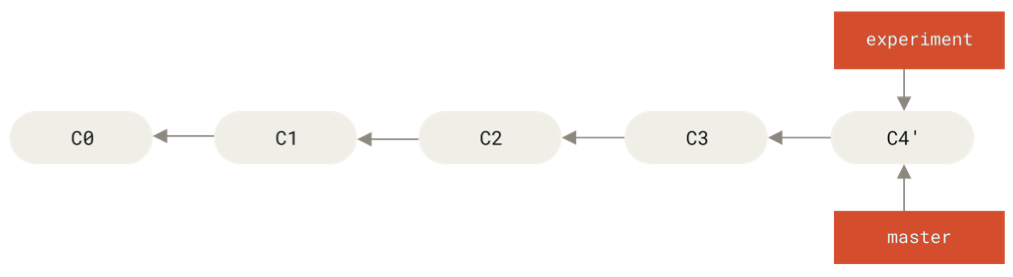

Starting out:

After running:

git checkout experiment

git rebase master

After running:

git checkout master

git merge experiment

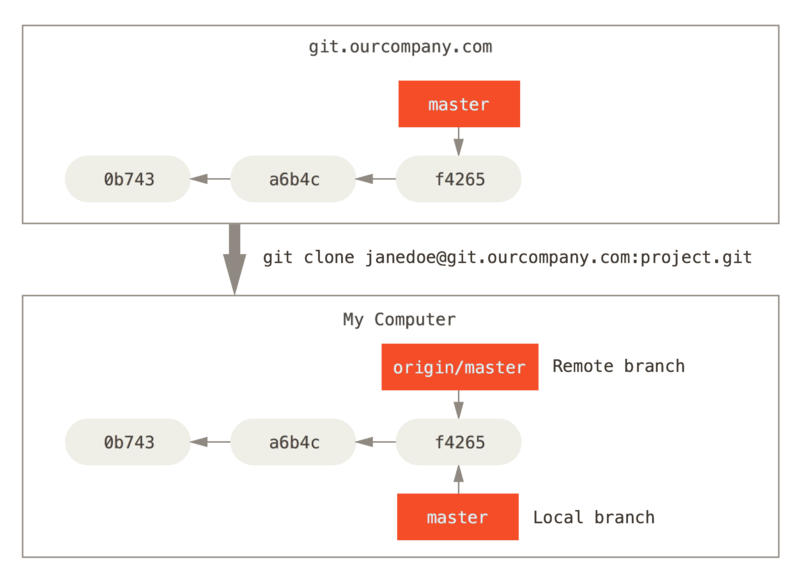

A remote repository is a version of the project that is hosted somewhere else (e.g. GitHub).

Just like your local repository, the remote repository is a collection of commits and branches.

Reading from and writing to remote repositories is how people collaborate on projects with git.

You can have more than one remote repository for a project.

Main issues in working with remotes are reading and writing commits and branches, and being able to refer to branches on the remote.

We will have a lot of different kinds of branches:

To see the remote servers corresponding to your project that you have

set up, use git remote, or git remote -v.

For example:

$ git clone https://github.com/schacon/ticgit

Cloning into 'ticgit'...

remote: Reusing existing pack: 1857, done.

remote: Total 1857 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

Receiving objects: 100% (1857/1857), 374.35 KiB | 268.00 KiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (772/772), done.

Checking connectivity... done.

$ cd ticgit

$ git remote

origin$ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/schacon/ticgit (fetch)

origin https://github.com/schacon/ticgit (push)If you had multiple remotes, you might get something like this:

$ cd grit

$ git remote -v

bakkdoor https://github.com/bakkdoor/grit (fetch)

bakkdoor https://github.com/bakkdoor/grit (push)

cho45 https://github.com/cho45/grit (fetch)

cho45 https://github.com/cho45/grit (push)

defunkt https://github.com/defunkt/grit (fetch)

defunkt https://github.com/defunkt/grit (push)

koke git://github.com/koke/grit.git (fetch)

koke git://github.com/koke/grit.git (push)

origin git@github.com:mojombo/grit.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:mojombo/grit.git (push)With git clone:

By default, if you run git clone <url>, git

will add <url> as a remote repository with the name

origin.

Nothing special about the name origin

With git remote add:

git remote add <shortname> <url> will add

<url> as a remote repository with the name

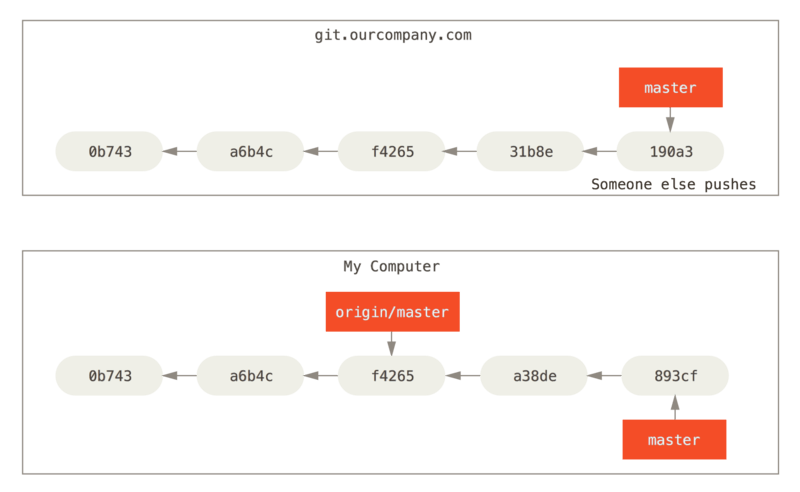

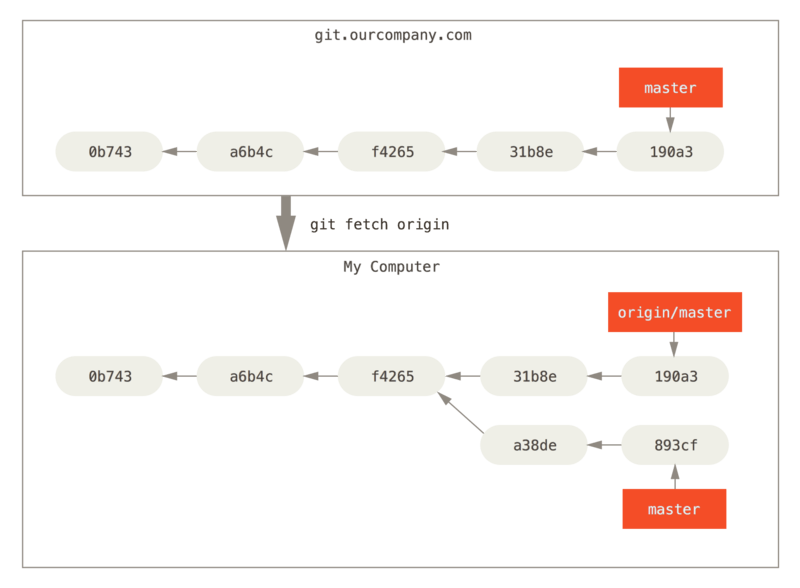

<shortname>To get new commits that have been added to a remote repository, run

git fetch <remote>

What happens?

Any commits that are on <remote> that you

don’t have are downloaded and added to your repository.

Remote-tracking branches are updated

Problem: how do we refer to branches in the remote? There’s nothing preventing the remote from having branches with the same name as our local branches but that point to different commits.

Solution: remote-tracking branches:

Have names of the form

<remote>/<branch-name>.

You can’t modify these, they refer to a branch in the remote repository.

If you want more information about a remote, you can use

git remote show <remote-name>.

For example:

$ git remote show origin

* remote origin

Fetch URL: https://github.com/schacon/ticgit

Push URL: https://github.com/schacon/ticgit

HEAD branch: master

Remote branches:

master tracked

dev-branch tracked

Local branch configured for 'git pull':

master merges with remote master

Local ref configured for 'git push':

master pushes to master (up to date)A more complicated example:

$ git remote show origin

* remote origin

URL: https://github.com/my-org/complex-project

Fetch URL: https://github.com/my-org/complex-project

Push URL: https://github.com/my-org/complex-project

HEAD branch: master

Remote branches:

master tracked

dev-branch tracked

markdown-strip tracked

issue-43 new (next fetch will store in remotes/origin)

issue-45 new (next fetch will store in remotes/origin)

refs/remotes/origin/issue-11 stale (use 'git remote prune' to remove)

Local branches configured for 'git pull':

dev-branch merges with remote dev-branch

master merges with remote master

Local refs configured for 'git push':

dev-branch pushes to dev-branch (up to date)

markdown-strip pushes to markdown-strip (up to date)

master pushes to master (up to date)Tracking branches: not the same as remote-tracking branches

When/how are they created?

<remote>/<branch-name>.main that tracks

origin/main.git checkout -b <branch> <remote>/<branch>

or git checkout --track <remote>/<branch-name>,

which will create a local branch called <branch-name>

that tracks <remote>/<branch-name>.What are they for?

Method 1: Explicitly naming the local and remote branches

git push <local-branch-name>:<remote-branch-name>

will push all the commits that are ancestors of

<local-branch-name> to the remote and will set

<remote>/<remote-branch-name> to point to the

commit that <local-branch-name> points to.<local-branch-name> and make

it the remote’s branch <remote-branch-name>git push <branch-name>.Method 2: If you are on a tracking branch

git push with no extra argumentsNote:

Setup: You are on a tracking branch, and you want to get any new commits from the upstream branch on the remote.

You can use git pull, which is usually equivalent to

git fetch plus

git merge <tracking-branch> <remote>/<upstream>,

where <tracking-branch> is the branch that you are

currently on, and <remote>/<upstream> is the

upstream branch that your <tracking-branch>

tracks.

GitHub is a site that hosts git repositories. There are two main collaboration workflows:

Notice that cloning and forking are different:

| Action | Happens where | You get write access? |

|---|---|---|

| Clone | On your local machine | Only if you already have permission |

| Fork | On GitHub | Yes, to your own copy |

Normally, if you want to work on a public repository that you don’t have push access to, you would

A Pull Request is a request for someone else to pull your branch. GitHub adds:

Even collaborators use PRs to get code review.

Both local and remote repositories are just sets of commits and branches.

Primary problem is how to refer to branches in the remote.

Defaults for pushing and pulling sometimes make things confusing.

GitHub adds collaboration tools (permissions, PRs, issues, reviews) on top of Git.

Fork + PR workflow makes it possible to contribute even without push access.