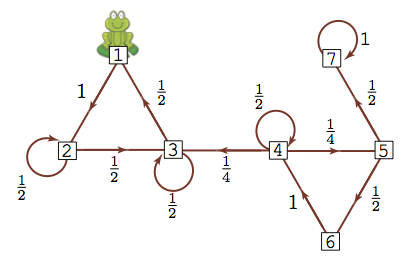

Let’s do the same thing: if we start the frog at different locations, compute the probability of being at any of the lily pads after 64 steps.

## 2^6-step probabilities, starting at 1

lambda = c(1, rep(0, 6))

lambda %*% pow_P(P_big, 6)

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7]

## [1,] 0.2 0.4 0.4 0 0 0 0

## 2^6-step probabilities, starting at 7

lambda = c(rep(0, 6), 1)

lambda %*% pow_P(P_big, 6)

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7]

## [1,] 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

## 2^6-step probabilities, starting at 6

lambda = c(rep(0, 5), 1, 0)

lambda %*% pow_P(P_big, 6)

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

## [1,] 0.1333333 0.2666667 0.2666667 1.905188e-09 6.499812e-10 4.435003e-10

## [,7]

## [1,] 0.3333333

round(pow_P(P_big, 6), digits = 2)

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7]

## [1,] 0.20 0.40 0.40 0 0 0 0.00

## [2,] 0.20 0.40 0.40 0 0 0 0.00

## [3,] 0.20 0.40 0.40 0 0 0 0.00

## [4,] 0.13 0.27 0.27 0 0 0 0.33

## [5,] 0.07 0.13 0.13 0 0 0 0.67

## [6,] 0.13 0.27 0.27 0 0 0 0.33

## [7,] 0.00 0.00 0.00 0 0 0 1.00