Monte Carlo methods: Approximate Bayesian Computation

Today: Approximate Bayesian Computation

Reading: Sisson, Fan, Beaumont, “Overview of Approximate Bayesian Computation”

Bayesian Statistics

Suppose we have data \(y_1,\ldots, y_n\) that we believe can be described by a probability model with parameters \(\theta\).

We also have a prior distribution on the parameters \(\theta\), describing our belief about the values of those parameters before seeing any of the data.

\[

\begin{align*}

y_i \mid \theta &\sim P(y_i \mid \theta), \quad i = 1,\ldots, n\\

\theta & \sim \pi(\theta)

\end{align*}

\]

Posterior distribution

By applying Bayes’ rule, we can compute the posterior distribution of the parameters given the data: \[

\begin{align*}

P(\theta \mid y_1,\ldots, y_n) &= \frac{P(y_1,\ldots, y_n \mid \theta)\pi(\theta)}{P(y_1,\ldots, y_n)}

\end{align*}

\]

We want to know as much about this distribution as possible.

For simple cases it is available in closed form

For more complicated cases our best hope is to draw samples of it

From those samples we can compute posterior means, variances, etc. using the Monte Carlo methods from last two classes.

One way of drawing samples from the posterior

Inputs:

A target posterior: \(P(\theta \mid y_{\text{obs}}) \propto P(y_{\text{obs}} \mid \theta) \pi(\theta)\)

A way of simulating from \(P(y_{\text{obs}} \mid \theta)\)

A prior on the parameters \(\pi(\theta)\)

Sampling: for \(i = 1,\ldots, N\):

Generate \(\theta^{(i)} \sim \pi(\theta)\)

Generate \(y^{(i)} \sim p(y \mid \theta^{(i)})\)

If \(y^{(i)} = y_{\text{obs}}\), accept \(\theta^{(i)}\)

Why does this work?

Our draws \((\theta^{(i)}, y^{(i)})\) are samples from the joint distribution \(P(\theta, y)\)

Keeping only the values for which \(y^{(i)} = y_{\text{obs}}\) is the definition of conditioning on \(y_{\text{obs}}\).

ABC: Simple Example

Bayesian analysis for a Poisson random variable.

Model is: \[

\begin{align*}

Y_i &\sim \text{Poisson}(\theta), \quad i = 1,\ldots, n \\

\theta &\sim \text{Gamma}(\alpha, \beta)

\end{align*}

\]

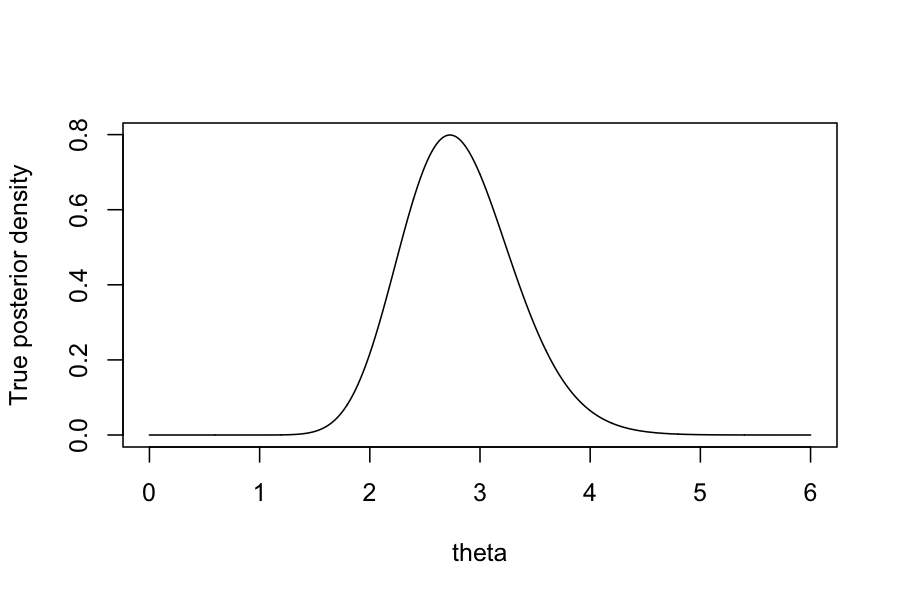

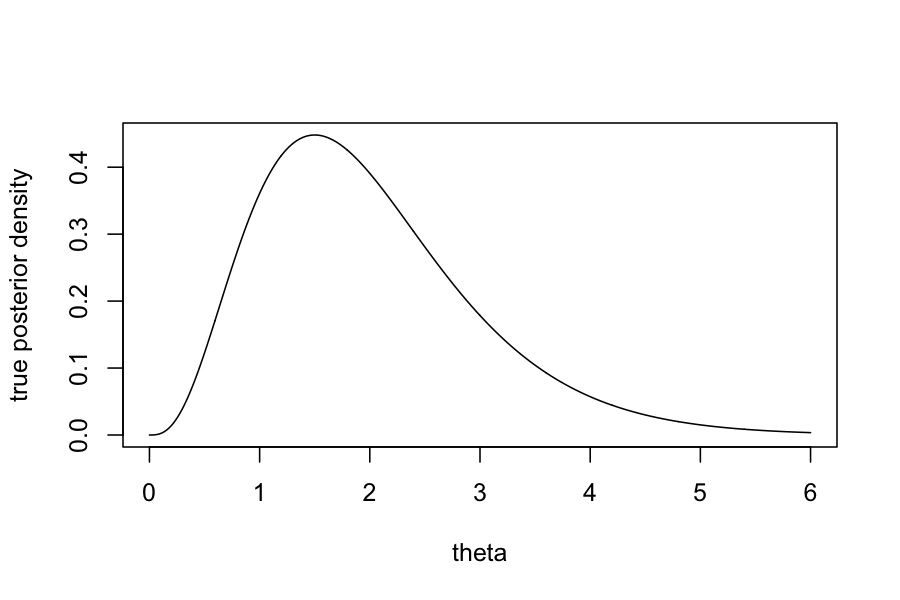

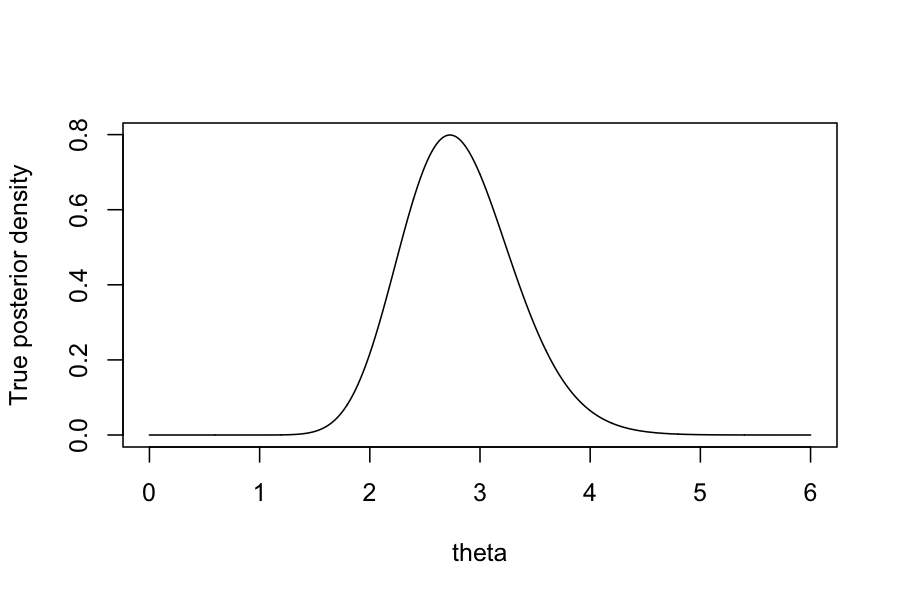

By Bayes rule, we can find in closed form that the posterior, \(P(\theta \mid Y_1, \ldots, Y_n)\) has a \(\text{Gamma}(\sum_{i=1}^n Y_i + \alpha, n + \beta)\) distribution.

Let’s pretend we can’t do that though, and try using ABC.

Set up a function for the approximate version of ABC:

generate_abc_sample_2 = function(observed_data,

summary_statistic,

prior_distribution,

data_generating_function,

epsilon) {

while(TRUE) {

theta = prior_distribution()

y = data_generating_function(theta)

if(abs(summary_statistic(y) - summary_statistic(observed_data)) < epsilon) {

return(theta)

}

}

}

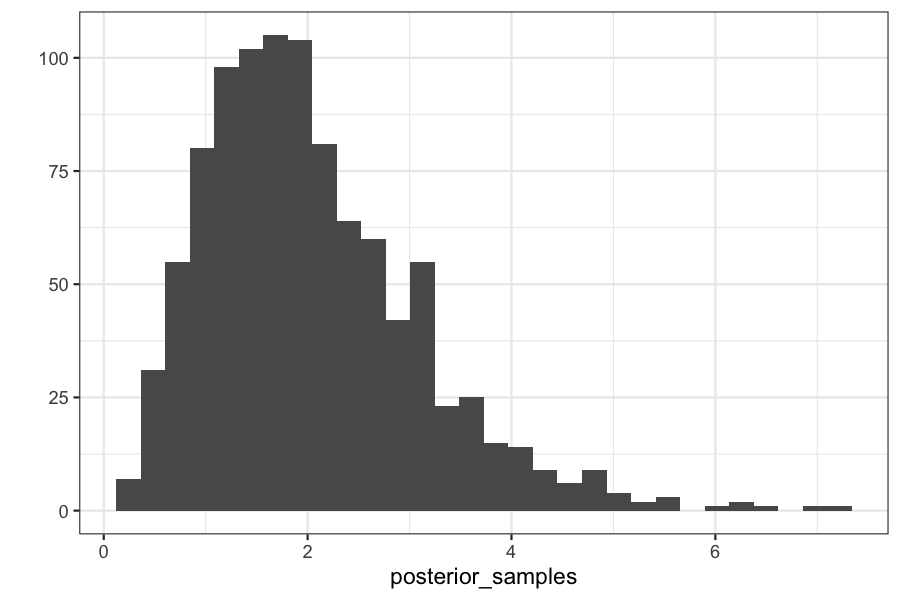

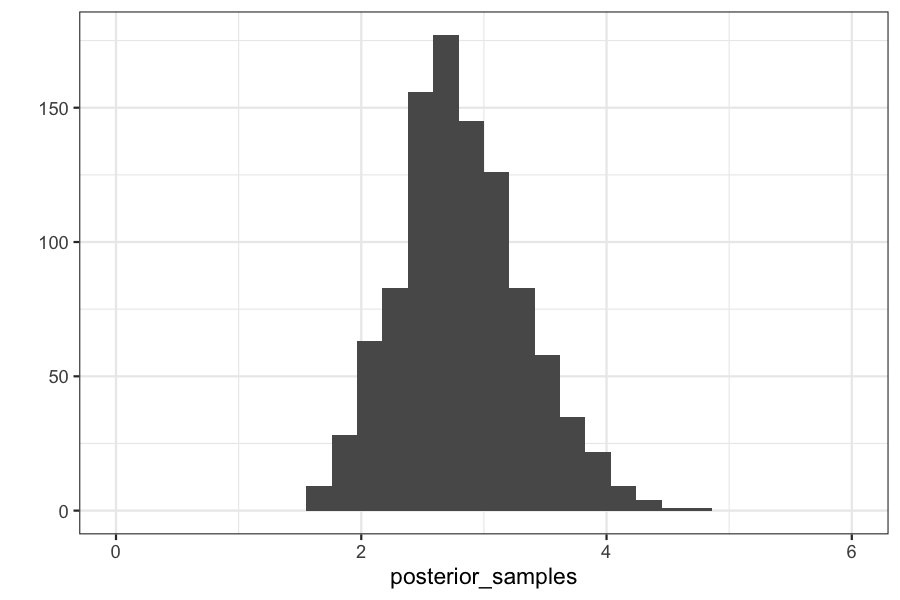

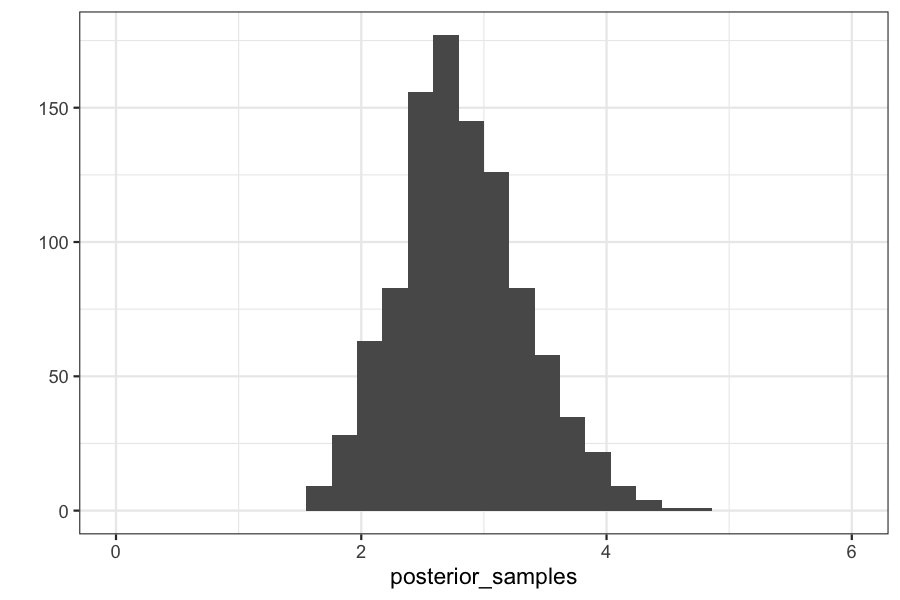

Checking on the posterior distributions:

qplot(posterior_samples) + xlim(c(0, max(theta_vec)))

## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

plot(dgamma(theta_vec, shape = 1 + sum(observed_data), rate = n_samples + 1) ~ x_vec, type = 'l', ylab = "True posterior density", xlab = "theta")