Start with three commits, two branches

Reading (if you want more detail):

Pro Git, Chapters 1, 2, 3, 10.

Basic idea:

Stores snapshots of the directory, these are commits

If you’ve changed some things and don’t like the results, you can go back to an older version and start over

You can easily display differences between states of the directory at different points in time

Allows multiple people to work on the same project

Allows for resolving simultaneous changes as easily as possible

We have a complete history of who changed what and why

Important conceptually are commits and branches

A commit records the state of the repository at a particular point in time

Contains:

Hash of the tree object for the top level directory

Hash of the parent commit

Meta-information about the commit (author, commit message, date, etc.)

You should think of git as storing a set of commits.

A branch is a pointer to one commit.

By default, you start off with a branch called master, but you can make more, and with any names you want.

There is nothing special about the master branch.

Problem: if you’re making changes (= adding commits), you probably want a pointer to the most recent commit. We would like branches to move when we make a new commit.

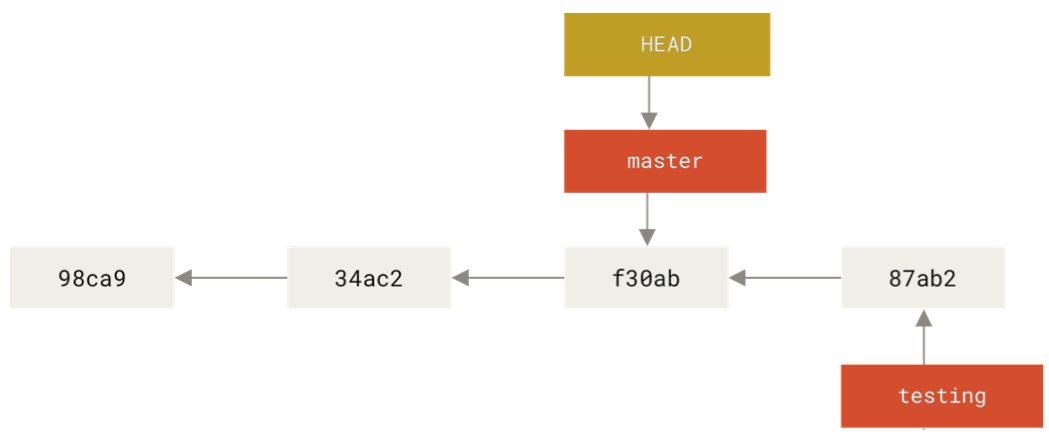

HEAD solves the problem of updating branches after commits.

HEAD is a pointer to a branch.

When you make a new commit, the branch HEAD points to moves to the new commit.

The checkout function allows you to change the branch HEAD points to.

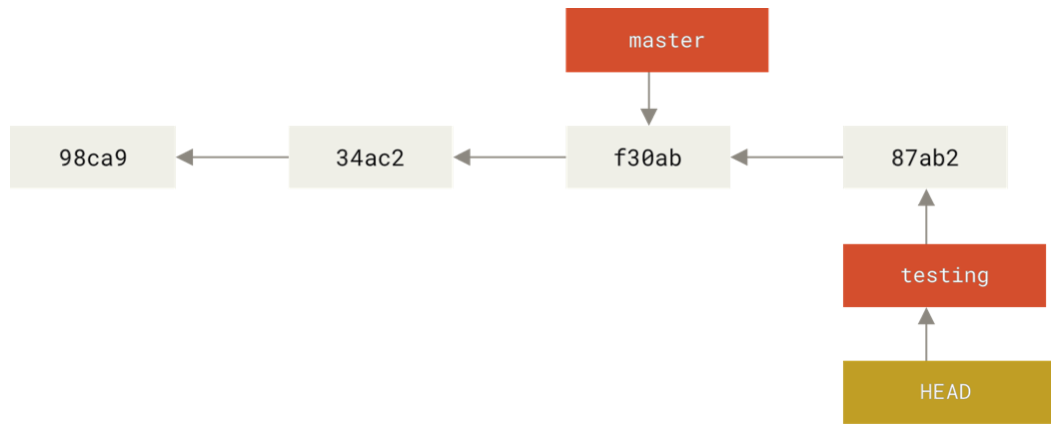

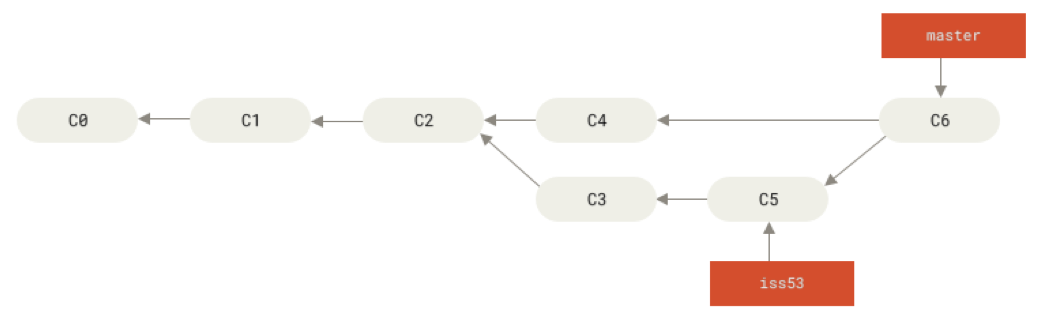

Start with three commits, two branches

Add a commit:

Switch branches with checkout:

Setup:

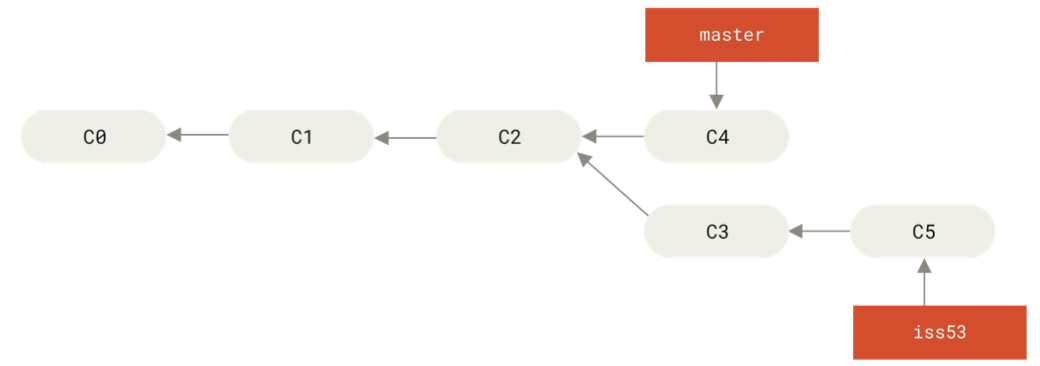

You have a branching commit history

You want to incorporate both sets of changes

Solutions:

Merge: Make a new commit with two parents

Rebase: Applies changes from one branch onto another

Starting out:

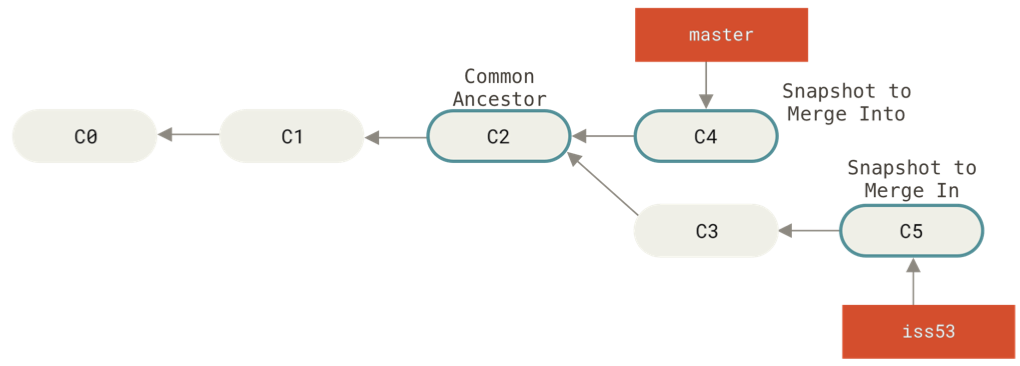

How we want the merge to look:

After running

git checkout master

git merge iss53

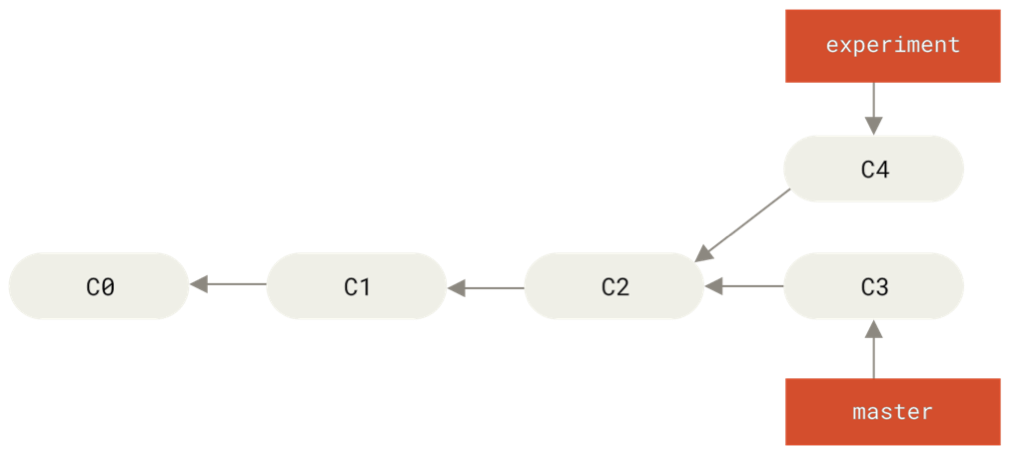

Rebasing branch2 onto branch1:

Find the most recent common ancestor of branch1 and branch2

Find all the differences between branch2 and the most recent common ancestor

Apply those changes to branch1

Starting out:

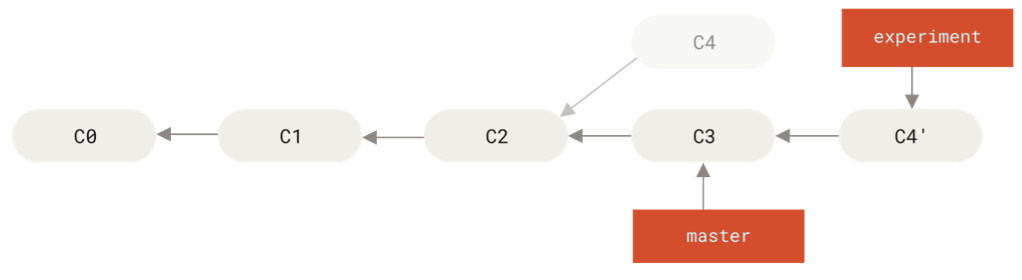

After running:

git checkout experiment

git rebase master

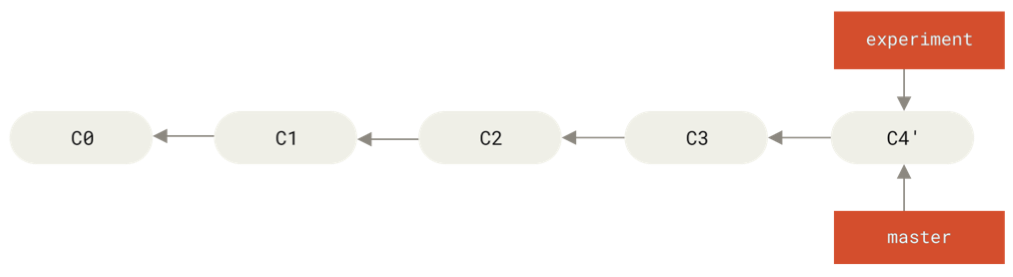

After running:

git checkout master

git merge experiment

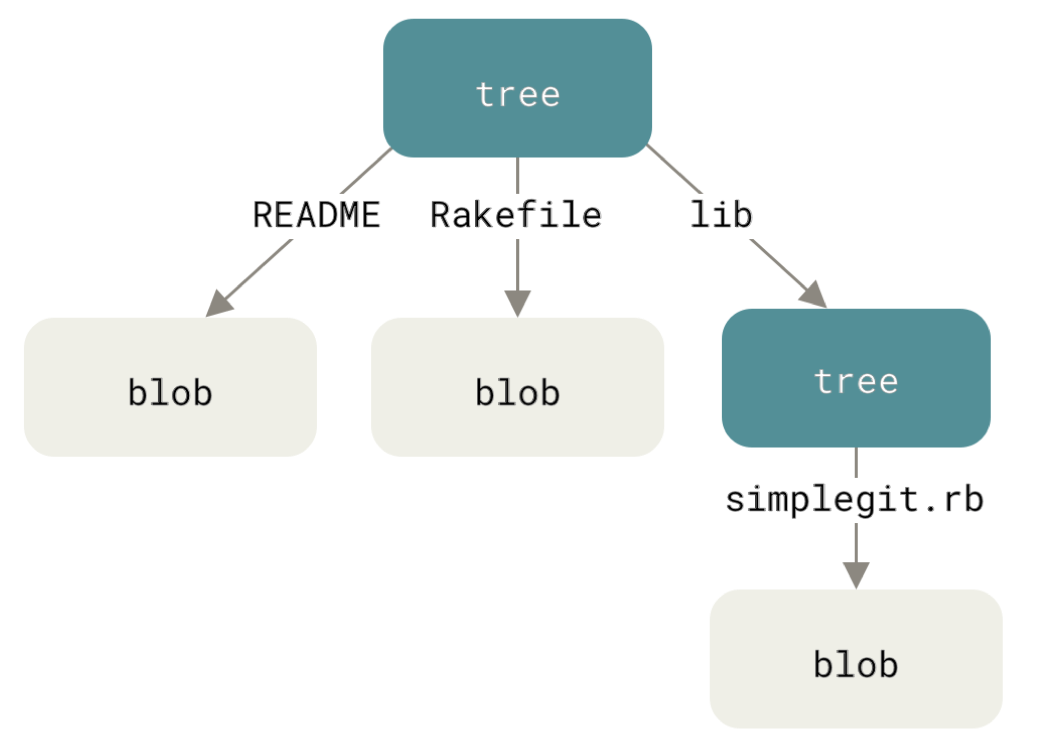

Three basic types of objects:

blobs: contents of a file

trees: an object describing the contents of a directory

commits: an object describing the state of the repository at a particular point in time

All these objects are stored by their hash

A hash is a tool from computer security for checking whether data has been tampered with

Git uses SHA1

This is a function that takes data of any size and produces a 20-byte hash value.

This is usually displayed as a 40-digit hexadecimal number.

Idea behind a hash function is that small perturbations in the data lead to large changes in the hash value, and the function is designed to be difficult to invert (if you’re given a hash value, it’s hard to create a file that has that value)

Every object is referred to by its hash value

Blobs store the contents of a file

Name is the hash value of the contents of the file

Blobs just store the contents of the file

Trees store the file name and the directory structure

To see the tree, you can use:

git cat-file -p master^{tree}And the output might look like this:

100644 blob 01b480b010b7fe66e312e1271dd24e128f3a0290 .gitmodules

100644 blob 1d17afb2a980076fc389f3d2747b0bfefd4df839 Dockerfile

100644 blob 716007c1456163b933cb086acae151fc6a24ca6d README.md

100644 blob 9af5513cf53dfbdedbc69ec43865dec054de0ccd SConstruct

040000 tree 100d47915afe22615ff111d390170c7265900b7a analysisConceptually, if we have a directory containing

README,

Rakefile,

A subdirectory called lib,

A file samplegit.rb in lib,

Git would store a snapshot of the directory as three blobs and two trees:

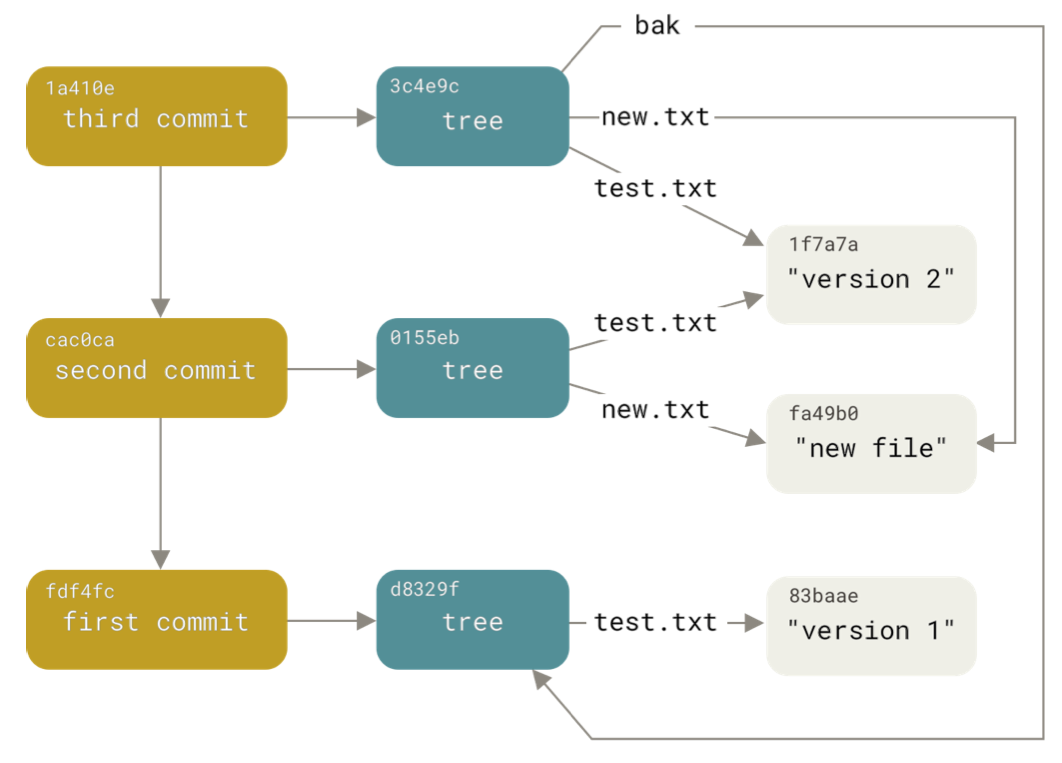

Commits are also referred to by their hashes.

They are files with information about the parent commit, the hash of the tree describing the directory structure for that commit, and some metadata about the commit.

Putting everything together, we get a graph that describes the files that were present at different commits:

Remember: a commit is a snapshot of the directory structure

You don’t necessarily want to record all of the changes you’ve made since the previous commit.

To allow you to specify which changes you want to record for the commit, git uses a staging area (also called the index).

When you modify files that you want to commit, you add them to the staging area.

Once you have the staging area in a state you like, you can commit the stages from the staging area and they are added to the repository.

For example:

git init test

cd test

git status

echo "test file" > test.txt

git statusNow we have one untracked file, which means it is not in the staging area.

If we run

git add test.txt

git statusWe get output

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: test.txt

which tells us that test.txt is now in the staging area.

We can now commit what we have in the staging area:

git commit -m "first commit"which will give us:

[master (root-commit) 8e9c4cc] first commit

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 test.txtThis tells us:

Our repository now contains a new commit, whose hash starts with 8e9c4cc

We’ve changed one file

We’ve added a new object to the repository, test.txt

A git repository contains a set of commits, which describe the contents of a directory at a certain point in time

The main things we want to be able to do are add new commits and move to different commits

A branch is just a name for a specific commit, and it allows us to move between different commits without referring to them by their name/hash